The wide availability and power density of 18650 lithium-ion cells have made them a good option for everything from electric cars to flashlights. [Theo] needed a new power source for his FPV drone goggles, so he designed his own power bank with a very compact charge controller.

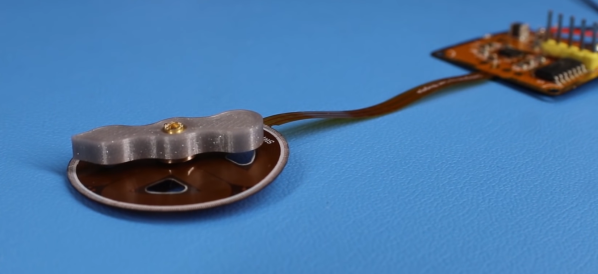

While [Theo] could charge the batteries with an RC battery charger, he preferred the convenience of one with a standard 5V micro USB input, and wanted battery level indication to avoid having the FPV goggles die unexpectedly mid-flight. When four 18650 cells are held in a cube arrangement, a 8x8x65 mm gap is formed between the cells. In this space [Theo] was able to fit a custom PCB with a micro USB jack, 1.3 mm power jack, BQ25606 charge controller, TPS61085 boost converter, and ATtiny MCU with LED for battery level feedback. The charge controller also allows 5V devices to be charged via USB, while the boost converter outputs 9V via the 1.3mm jack for [Theo]’s FPV goggles. Everything fits inside a nice compact 3D printed enclosure.

The project was not without hiccups. After ordering and building the PCB he discovered some minor PCB layout mistakes, and realized the boost converted could only output 600mA at 9V, which was not enough for his more power-hungry googles. He plans to fix this in the next version.

We’ve seen custom power banks in quite a few shapes and sizes, including one that runs on power tool batteries (which probably also have 18650s inside) and one that has just about every output you could want, including AC and wireless QI charging.