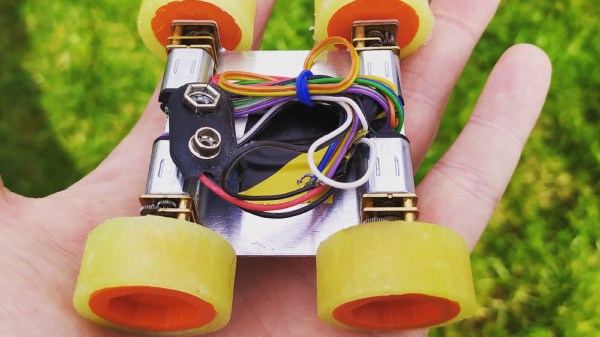

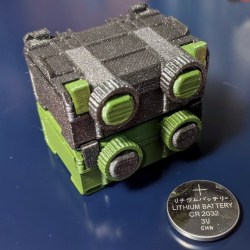

For people who work with wheeled robots or RC vehicles, sooner or later one gets interested in making custom tires instead of dealing with whatever is available off the shelf. [concreted0g]’s preferred method is to design and 3D print wheel hubs, then cast some custom silicone tires to fit over them. Of course, the devil is in the details and this process can be a bit messy, so he’s shared useful tips on how to get reliable results with simple materials.

The casting material is cheap silicone caulking from a hardware store, and color can be added with a small amount of cheap acrylic paint. A few drops of glycerin added to the silicone thins it out slightly and helps it flow into a mold better. Mix well (the paint will also serve as a visual indicator of how well it is mixed), then scoop the mixture into the mold while trying to avoid creating air pockets. If your mold is in two pieces, assemble the mold and remove any overflow, then let it sit undisturbed for at least several hours while it cures.

The casting material is cheap silicone caulking from a hardware store, and color can be added with a small amount of cheap acrylic paint. A few drops of glycerin added to the silicone thins it out slightly and helps it flow into a mold better. Mix well (the paint will also serve as a visual indicator of how well it is mixed), then scoop the mixture into the mold while trying to avoid creating air pockets. If your mold is in two pieces, assemble the mold and remove any overflow, then let it sit undisturbed for at least several hours while it cures.

Mounting the resulting tire to a wheel hub can be done with a thin film of super glue, which seems to work perfectly well for small tires and is easy to apply.

The rules are going to be a bit different for big objects. We know that silicone caulking can have difficulty fully curing when it’s applied thickly, especially when sealed into a mold with little to no airflow. In such cases, adding cornstarch (in about a 5:1 ratio of silicone to cornstarch by volume) is all that it takes to cure even thick wads of goop in less than an hour. Stirring cornstarch in tends to introduce more air bubbles into the mixture, but for larger pieces that can be an acceptable tradeoff. Cheap silicone caulking is versatile stuff, one just needs to know what to expect, and take a few steps to deal with the messiness.

Need something tougher? Maybe check out using slices of automotive silicone hose for robot wheels to get something that works just as well, but is a lot more durable.