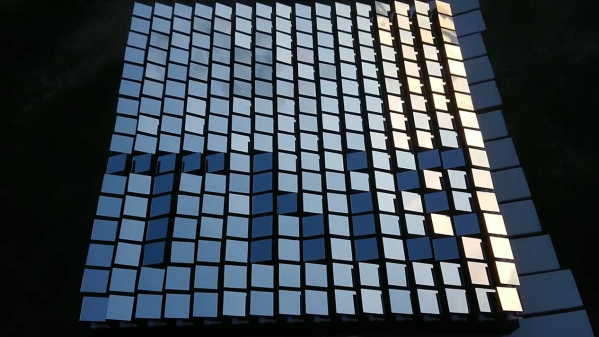

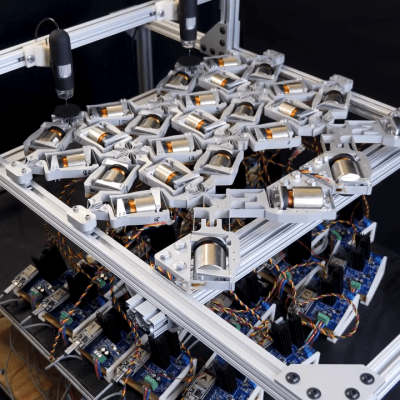

Here’s an unusual concept: a computer-guided mechanical neural network (video, embedded below.) Why would one want a mechanical neural network? It’s essentially a tool to explore what it would take to make physical materials work in nonstandard ways. The main part is a lattice of interlinked mechanical components. When one applies a certain force in a certain direction on one end, it causes the lattice to deform in a non-intuitive way on the other end.

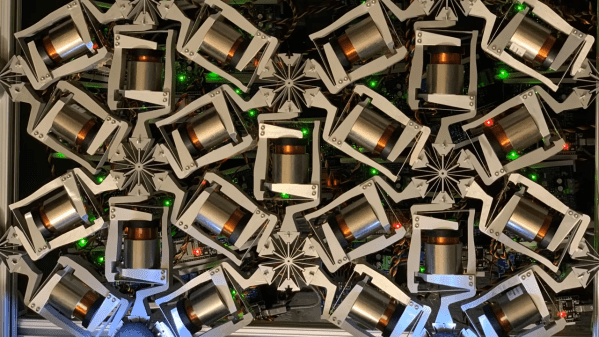

To make this happen, individual mechanical elements in the lattice need to have their compliance carefully tuned under the guidance of a computer system. The mechanisms shown can be adjusted on demand while force is applied and cameras monitor the results.

To make this happen, individual mechanical elements in the lattice need to have their compliance carefully tuned under the guidance of a computer system. The mechanisms shown can be adjusted on demand while force is applied and cameras monitor the results.

This feedback loop allows researchers to use the same techniques for training neural networks that are used in machine learning applications. Ultimately, a lattice can be configured in such a way that when side A is pressed like this, side B moves like that.

We’ve seen compliant structures that move in unexpected ways before, and they are always fascinating. One example is this 3D-printed door latch that translates a twisting motion into a linear one. Research into physical neural networks seems like it might open the door to more complex systems, or provide insights into metamaterial design.

You can watch the video below just under the page break, or if you prefer, skip the intro and jump straight into How It Works at [2:32].

Continue reading “Physical Neural Network Can Be Trained Like A Digital One”