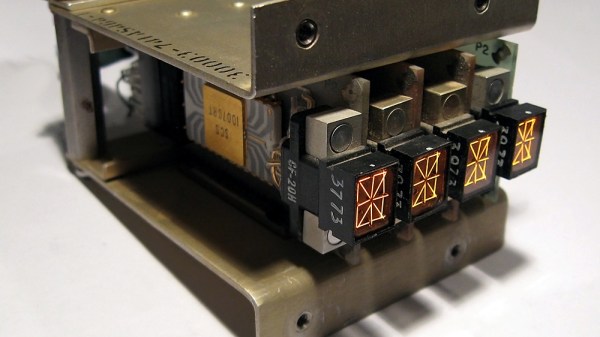

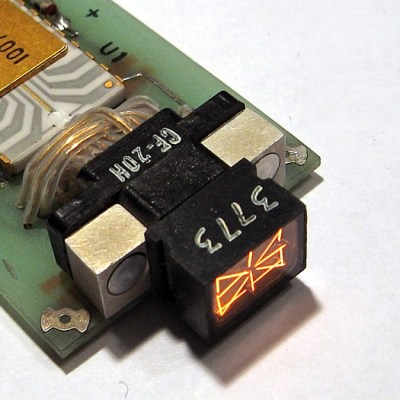

It’s easy to take display technology for granted nowadays, but the ability to display data in a human-readable way was not always easy. This is demonstrated well by the Pinlite 30003 Alphanumeric Display Module, a four-character display that was pure luxury for its time.

Not only were the 17 segments that make up each display capable of showing any letter or number, but they were even daylight-readable! Each of those 17 segments is an incandescent lamp filament, which is how the required brightness was achieved. The sturdy module shown here holds four such displays, each of which is on its own pluggable board with a dedicated character decoder chip directly behind it.

As [AnubisTTL] points out, the resulting unit is bulky, has terrible character spacing, and was no doubt very costly. By today’s standards, it is almost unimaginably heavy, hot, and impractical. But before high-brightness LEDs were a thing, a daylight-readable alphanumeric character display was really something special. It would absolutely have been worth the money and effort to the right people.

Before small and efficient displays were commonplace, the solution to the problem of how to display data efficiently and in an easy-to-read format took a lot of really unusual (and clever) turns as engineers worked around the limitations of the time. This resulted in oddities like the SD-11 Sphericular Display, which is mostly empty space on the inside. Another great example is the Eidophor, a projector from before projectors were even a thing.