The degree to which computed tomography has been a boon to medical science is hard to overstate. CT scans give doctors a look inside the body that gives far more information about the spatial relationship of structures than a plain X-ray can. And as it turns out, CT scans are pretty handy for reverse engineering mystery electronic modules, too.

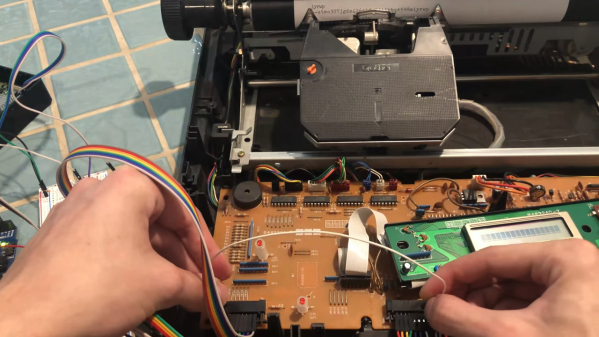

The fact that the mystery module in question is from Apollo-era test hardware leaves little room for surprise that [Ken Shirriff] is the person behind this fascinating little project. You’ll recall that [Ken] recently radiographically reverse engineered a pluggable module of unknown nature, using plain X-ray images taken at different angles to determine that the undocumented Motorola module was stuffed full of discrete components that formed part of a square wave to sine wave converter.

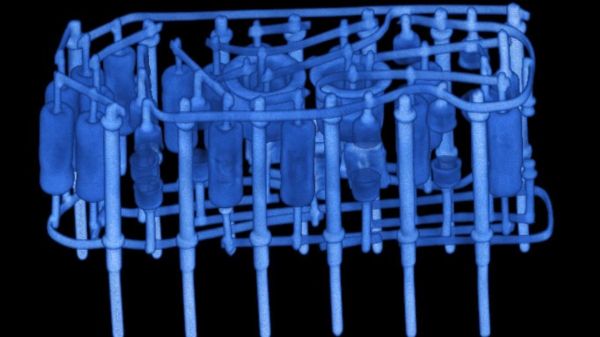

The module for this project, a flip-flop from Motorola and in the same form factor, went into an industrial CT scanner from an outfit called Lumafield, where X-rays were taken from multiple angles. The images were reassembled into a three-dimensional view by the scanner’s software, which gave a stunningly clear view of the components embedded within the module’s epoxy body. The cordwood construction method is obvious, and it’s pretty easy to tell what each component is. The transistors are obvious, as are the capacitors and diodes. The resistors were a little more subtle, though — careful examination revealed that some are carbon composition, while others are carbon film. It’s even possible to pick out which diodes are Zeners.

The CT scan data, along with some more traditional probing for component values, let [Ken] reverse engineer the whole circuit, which turned out to be a little different than a regular J-K flip-flop. Getting a non-destructive look inside feels a little like sitting alongside the engineers who originally built these things, which is pretty cool.