After all the fuss and bother along the way, it seems a bit anticlimactic now that the James Webb Space Telescope has arrived at its forever home orbiting around L2. The observatory finished its trip on schedule, arriving on January 24 in its fully deployed state, after a one-month journey and a couple of hundred single-point failure deployments. The next phase of the mission is commissioning, and is a somewhat more sedate and far less perilous process of tweaking and trimming the optical systems, and getting the telescope and its sensors down to operating temperature. The commissioning phase will take five or six months, so don’t count on any new desktop photos until summer at the earliest. Until then, enjoy the video below which answers some of the questions we had about what Webb can actually see — here’s hoping there’s not much interesting to see approximately in the plane of the ecliptic.

Author: Dan Maloney3373 Articles

Laundry Bot Tackles The Tedium Of T-Shirt Folding

Roomba aside, domestic robots are still in search of the killer app they need to really take off. For the other kind of home automation to succeed, designers are going to have to find the most odious domestic task and make it go away at the push of the button. A T-shirt folding robot is probably a good first step.

First and foremost, hats off to [] for his copious documentation on this project. Not only are complete instructions for building the laundry bot listed, but there’s also a full use-case analysis and even a complete exploration of prior art in the space. [Stefano]’s exhaustive analysis led to a set of stepper-actuated panels, laser-cut from thin plywood, and arranged to make the series of folds needed to take a T-shirt from flat to folded in just a few seconds.

The video below shows the folder in action, and while it’s not especially fast right now, we’ll chalk that up to still being under development. We can see a few areas for improvement; making the panels from acrylic might make the folded shirt slide off the bot better, and pneumatic actuators might make for quicker movements and sharper folds. The challenges to real-world laundry folding are real, but this is a great start, and we’ll be on the lookout for improvements.

Continue reading “Laundry Bot Tackles The Tedium Of T-Shirt Folding”

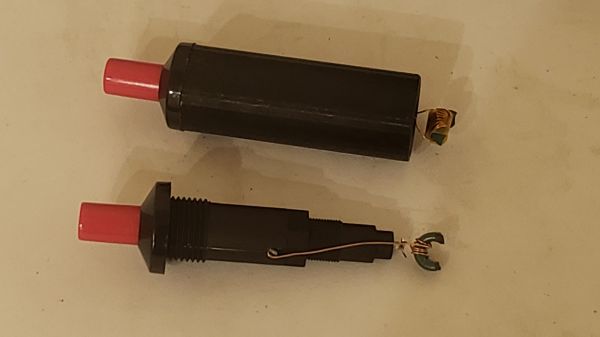

Blast Chips With This BBQ Lighter Fault Injection Tool

Looking to get into fault injection for your reverse engineering projects, but don’t have the cash to lay out for the necessary hardware? Fear not, for the tools to glitch a chip may be as close as the nearest barbecue grill.

If you don’t know what chip glitching is, perhaps a primer is in order. Glitching, more formally known as electromagnetic fault injection (EMFI), or simply fault injection, is a technique that uses a pulse of electromagnetic energy to induce a fault in a running microcontroller or microprocessor. If the pulse occurs at just the right time, it may force the processor to skip an instruction, leaving the system in a potentially exploitable state.

EMFI tools are commercially available — we even recently featured a kit to build your own — but [rqu]’s homebrew version is decidedly simpler and cheaper than just about anything else. It consists of a piezoelectric gas grill igniter, a little bit of enameled magnet wire, and half of a small toroidal ferrite core. The core fragment gets a few turns of wire, which then gets soldered to the terminals on the igniter. Pressing the button generates a high-voltage pulse, which gets turned into an electromagnetic pulse by the coil. There’s a video of the tool in use in the Twitter thread, showing it easily glitching a PIC running a simple loop program.

To be sure, a tool as simple as this won’t do the trick in every situation, but it’s a cheap way to start exploring the potential of fault injection.

Thanks to [Jonas] for the tip.

SHERLOC And The Search For Life On Mars

Humanity has been wondering about whether life exists beyond our little backwater planet for so long that we’ve developed a kind of cultural bias as to how the answer to this central question will be revealed. Most of us probably imagine that NASA or some other space agency will schedule a press conference, an assembled panel of scientific luminaries will announce the findings, and newspapers around the world will blare “WE ARE NOT ALONE!” headlines. We’ve all seen that movie before, so that’s the way it has to be, right?

Probably not. Short of an improbable event like an alien spacecraft landing while a Google Street View car was driving by or receiving an unambiguously intelligent radio message from the stars, the conclusion that life exists now or once did outside our particular gravity well is likely to be reached in a piecewise process, an accretion of evidence built up over a long time until on balance, the only reasonable conclusion is that we are not alone. And that’s exactly what the announcement at the end of last year that the Mars rover Perseverance had discovered evidence of organic molecules in the rocks of Jezero crater was — another piece of the puzzle, and another step toward answering the fundamental question of the uniqueness of life.

Discovering organic molecules on Mars is far from proof that life once existed there. But it’s a step on the way, as well as a great excuse to look into the scientific principles and engineering of the instruments that made this discovery possible — the whimsically named SHERLOC and WATSON.

Compliant Mechanisms Hack Chat

Join us on Wednesday, January 26 at noon Pacific for the Compliant Mechanisms Hack Chat with Amy Qian!

When it comes to putting together complex mechanisms, we tend to think in a traditional design language that includes elements like bearings, bushings, axles, pulleys — anything that makes it possible for separate rigid bodies to move against each other. That works fine in a lot of cases — our cars wouldn’t get very far without such elements — but there are simpler ways to transmit force and motion, like compliant mechanisms.

Compliant mechanisms show up in countless products, from the living hinge on a cheap plastic box to the nanoscale linkages etched into silicon inside a MEMS accelerometer. They reduce complexity by putting the elasticity of materials to work and by reducing the number of parts it takes to create an assembly. And they can help make your projects easier and cheaper to build — if you know the secrets of their design.

Amy Qian, from the Amy Makes Stuff channel on YouTube, is a mechanical engineer with an interest in compliant mechanisms, so much so that she ran a workshop about them at the 2019 Superconference. She’ll stop by the Hack Chat to share some of what she’s learned about compliant mechanisms, and to help us all build a little flexibility into our designs.

Amy Qian, from the Amy Makes Stuff channel on YouTube, is a mechanical engineer with an interest in compliant mechanisms, so much so that she ran a workshop about them at the 2019 Superconference. She’ll stop by the Hack Chat to share some of what she’s learned about compliant mechanisms, and to help us all build a little flexibility into our designs.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, January 26 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Hackaday Links: January 23, 2022

When Tonga’s Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha’apai volcano erupted on January 15, one hacker in the UK knew just what to do. Sandy Macdonald from York quickly cobbled together a Raspberry Pi and a pressure/humidity sensor board and added a little code to create a recording barometer. The idea was to see if the shock wave from the eruption would be detectable over 16,000 km away — and surprise, surprise, it was! It took more than 14 hours to reach Sandy’s impromptu recording station, but the data clearly show a rapid pulse of increasing pressure as the shockwave approached, and a decreased pressure as it passed. What’s more, the shock wave that traveled the “other way” around the planet was detectable too, about seven hours after the first event. In fact, data gathered through the 19th clearly show three full passes of the shockwaves. We just find this fascinating, and applaud Sandy for the presence of mind to throw this together when news of the eruption came out.

Good news for professional astronomers and others with eyes turned skyward — it seems like the ever-expanding Starlink satellite constellation isn’t going to kill ground-based observation. At least that’s the conclusion of a team using the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at the Palomar Observatory outside San Diego. ZTF is designed to catalog anything that blinks, flashes, or explodes in the night sky, making it perfect to detect the streaks from the 1,800-odd Starlink satellites currently in orbit. They analyzed the number of satellite transients captured in ZTF images, and found that fully 20 percent of images show streaks now, as opposed to 0.5 percent back in 2019 when the constellation was much smaller. They conclude that at the 10,000 satellite full build-out, essentially every ZTF image will have a streak in it, but since the artifacts are tiny and well-characterized, they really won’t hinder the science to any appreciable degree.

Speaking of space, we finally have a bit of insight into the causes of space anemia. The 10% to 12% decrease in red blood cells in astronauts during their first ten days in space has been well known since the dawn of the Space Age, but the causes had never really been clear. It was assumed that the anemia was a result of the shifting of fluids in microgravity, but nobody really knew for sure until doing a six-month study on fourteen ISS astronauts. They used exhaled carbon monoxide as a proxy for the destruction of red blood cells (RBCs) — one molecule of CO is liberated for each hemoglobin molecule that’s destroyed — and found that the destruction of RBCs is a primary effect of being in space. Luckily, there appears to be a limit to how many RBCs are lost in space, so the astronauts didn’t suffer from complications of severe anemia while in space. Once they came back to gravity, the anemia reversed, albeit slowly and with up to a year of measurable changes to their blood.

From the “Better Late Than Never” department, we see that this week that Wired finally featured Hackaday Superfriend Sam Zeloof and his homemade integrated circuits. We’re glad to see Sam get coverage — the story was also picked up by Ars Technica — but it’s clear that nobody at either outfit reads Hackaday, since we’ve been featuring Sam since we first heard about his garage fab in 2017. That was back when Sam was still “just” making transistors; since then, we’ve featured some of his lab upgrades, watched him delve into electron beam lithography, and broke the story on his first legit integrated circuit. Along the way, we managed to coax him out to Supercon in 2019 where he gave both a talk and an interview.

And finally, if you’re in the mood for a contest, why not check out WIZNet’s Ethernet HAT contest? The idea is to explore what a Raspberry Pi Pico with Ethernet attached is good for. WIZNet has two flavors of board: one is an Ethernet HAT for the Pico, while the other is as RP2040 with built-in Ethernet. The good news is, if you submit an idea, they’ll send you a board for free. We love it when someone from the Hackaday community wins a contest, so if you enter, be sure to let us know. And hurry — submissions close January 31.

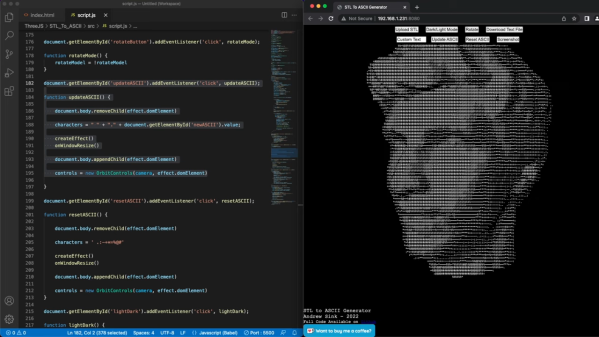

Online Tool Turns STLs Into 3D ASCII Art

If you look hard enough, most of the projects we feature on these pages have some practical value. They may seem frivolous, but there’s usually something that compelled the hacker to commit time and effort to its doing. That doesn’t mean we don’t get our share of just-for-funsies projects, of course, which certainly describes this online 3D ASCII art generator.

But wait — maybe that’s not quite right. After all, [Andrew Sink] put a lot of time into the code for this, and for its predecessor, his automatic 3D low-poly generator. That project led to the current work, which like before takes an STL model as input, this time turning it into an ASCII art render. The character set used for shading the model is customizable; with the default set, the shading is surprisingly good, though. You can also swap to a black-on-white theme if you like, navigate around the model with the mouse, and even export the ASCII art as either a PNG or as a raw text file, no doubt suitable to send to your tractor-feed printer.

[Andrew]’s code, which is all up on GitHub, makes liberal use of the three.js library, so maybe stretching his 3D JavaScript skills is really the hidden practical aspect of this one. Not that it needs one — we think it’s cool just for the gee-whiz factor.