It’s a sign of the times: the first day of the 33rd Chaos Communications Congress (33C3) included two talks related to assuring that your own computer wasn’t being turned against you. The two talks are respectively practical and idealistic, realizable today and a work that’s still in the idea stage.

In the first talk, [Trammell Hudson] presented his Heads open-source firmware bootloader and minimal Linux for laptops and servers. The name is a gag: the Tails Linux distribution lets you operate without leaving any trace, while Heads lets you run a system that you can be reasonably sure is secure.

It uses coreboot, kexec, and QubesOS, cutting off BIOS-based hacking tools at the root. If you’re worried about sketchy BIOS rootkits, this is a solution. (And if you think that this is paranoia, you haven’t been following the news in the last few years, and probably need to watch this talk.) [Trammell]’s Heads distribution is a collection of the best tools currently available, and it’s something you can do now, although it’s not going to be easy.

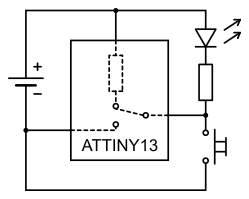

Carrying out the ideas fleshed out in the second talk is even harder — in fact, impossible at the moment. But that’s not to say that it’s not a neat idea. [Jaseg] starts out with the premise that the CPU itself is not to be trusted. Again, this is sadly not so far-fetched these days. Non-open blobs of firmware abound, and if you’re really concerned with the privacy of your communications, you don’t want the CPU (or Intel’s management engine) to get its hands on your plaintext.

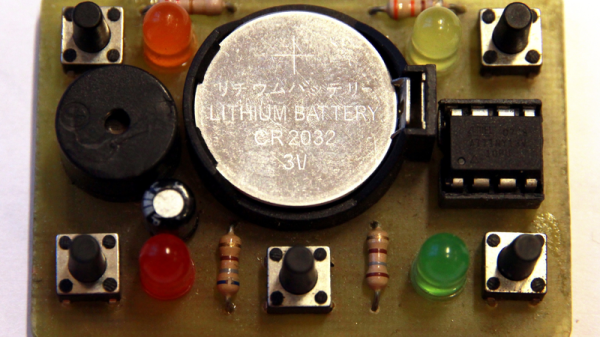

[Jaseg]’s solution is to interpose a device, probably made with a reasonably powerful FPGA and running open-source, inspectable code, between the CPU and the screen and keyboard. For critical text, like e-mail for example, the CPU will deal only in ciphertext. The FPGA, via graphics cues, will know which region of the screen is to be decrypted, and will send the plaintext out to the screen directly. Unless someone’s physically between the FPGA and your screen or keyboard, this should be unsniffable.

As with all early-stage ideas, the devil will be in the details here. It’s not yet worked out how to know when the keyboard needs to be encoded before passing the keystrokes on to the CPU, for instance. But the idea is very interesting, and places the trust boundary about as close to the user as possible, at input and output.