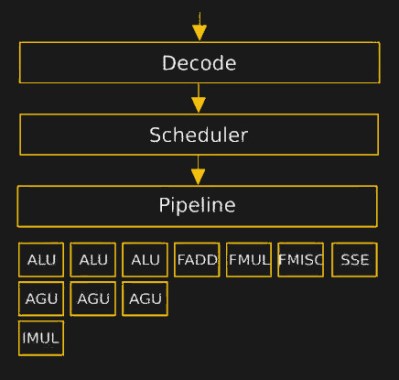

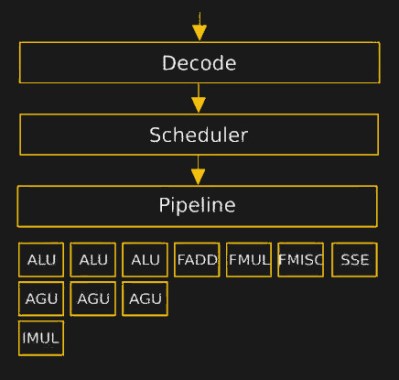

Inside every modern CPU since the Intel Pentium fdiv bug, assembly instructions aren’t a one-to-one mapping to what the CPU actually does. Inside the CPU, there is a decoder that turns assembly into even more primitive instructions that are fed into the CPU’s internal scheduler and pipeline. The code that drives the decoder is the CPU’s microcode, and it lives in ROM that’s normally inaccessible. But microcode patches have been deployed in the past to fix up CPU hardware bugs, so it’s certainly writeable. That’s practically an invitation, right? At least a group from the Ruhr University Bochum took it as such, and started hacking on the microcode in the AMD K8 and K10 processors.

The hurdles to playing around in the microcode are daunting. It turns assembly language into something, but the instruction set that the inner CPU, ALU, et al use was completely unknown. [Philip] walked us through their first line of attack, which was essentially guessing in the dark. First they mapped out where each x86 assembly codes went in microcode ROM. Using this information, and the ability to update the microcode, they could load and execute arbitrary microcode. They still didn’t know anything about the microcode, but they knew how to run it.

The hurdles to playing around in the microcode are daunting. It turns assembly language into something, but the instruction set that the inner CPU, ALU, et al use was completely unknown. [Philip] walked us through their first line of attack, which was essentially guessing in the dark. First they mapped out where each x86 assembly codes went in microcode ROM. Using this information, and the ability to update the microcode, they could load and execute arbitrary microcode. They still didn’t know anything about the microcode, but they knew how to run it.

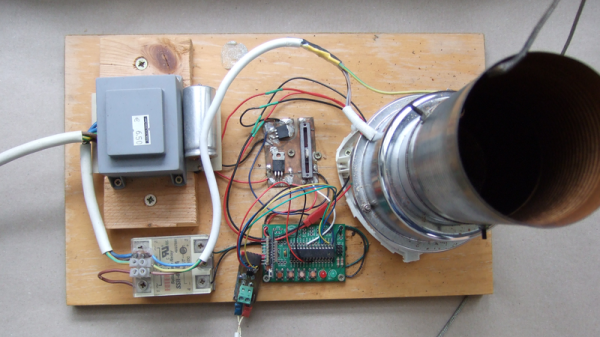

So they started uploading random microcode to see what it did. This random microcode crashed almost every time. The rest of the time, there was no difference between the input and output states. But then, after a week of running, a breakthrough: the microcode XOR’ed. From this, they found out the syntax of the command and began to discover more commands through trial and error. Quite late in the game, they went on to take the chip apart and read out the ROM contents with a microscope and OCR software, at least well enough to verify that some of the microcode operations were burned in ROM.

The result was 29 microcode operations including logic, arithmetic, load, and store commands — enough to start writing microcode code. The first microcode programs written helped with further discovery, naturally. But before long, they wrote microcode backdoors that triggered when a given calculation was performed, and stealthy trojans that exfiltrate data encrypted or “undetectably” through introducing faults programmatically into calculations. This means nearly undetectable malware that’s resident inside the CPU. (And you think the Intel Management Engine hacks made you paranoid!)

[Benjamin] then bravely stepped us through the browser-based attack live, first in a debugger where we could verify that their custom microcode was being triggered, and then outside of the debugger where suddenly

[Benjamin] then bravely stepped us through the browser-based attack live, first in a debugger where we could verify that their custom microcode was being triggered, and then outside of the debugger where suddenly xcalc popped up. What launched the program? Calculating a particular number on a website from inside an unmodified browser.

He also demonstrated the introduction of a simple mathematical error into the microcode that made an encryption routine fail when another particular multiplication was done. While this may not sound like much, if you paid attention in the talk on revealing keys based on a single infrequent bit error, you’d see that this is essentially a few million times more powerful because the error occurs every time.

The team isn’t done with their microcode explorations, and there’s still a lot more of the command set left to discover. So take this as a proof of concept that nearly completely undetectable trojans could exist in the microcode that runs between the compiled code and the CPU on your machine. But, more playfully, it’s also an invitation to start exploring yourself. It’s not every day that an entirely new frontier in computer hacking is bust open.

The hurdles to playing around in the microcode are daunting. It turns assembly language into something, but the instruction set that the inner CPU, ALU, et al use was completely unknown. [Philip] walked us through their first line of attack, which was essentially guessing in the dark. First they mapped out where each x86 assembly codes went in microcode ROM. Using this information, and the ability to update the microcode, they could load and execute arbitrary microcode. They still didn’t know anything about the microcode, but they knew how to run it.

The hurdles to playing around in the microcode are daunting. It turns assembly language into something, but the instruction set that the inner CPU, ALU, et al use was completely unknown. [Philip] walked us through their first line of attack, which was essentially guessing in the dark. First they mapped out where each x86 assembly codes went in microcode ROM. Using this information, and the ability to update the microcode, they could load and execute arbitrary microcode. They still didn’t know anything about the microcode, but they knew how to run it.