For modern students, the spiral notebook has given way to the laptop and the pocket calculator has been supplanted by the smart phone. We’re not just talking about high school and college, either. Today, the education of even grade school children is intrinsically linked with technology. While some might question the wisdom of moving away from the pencil and pad at such a young age, there’s little question that all the kids stuck at home right now due to COVID-19 would have had a much harder time transitioning to remote learning otherwise.

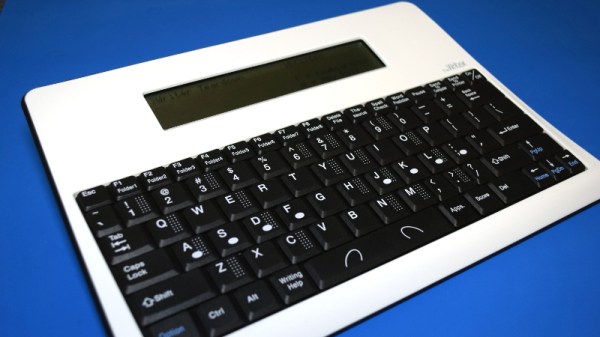

But that certainly wasn’t the case when Advanced Keyboard Technologies released the Writer in 2003. Back then, five years before the first netbooks hit the market, you’d be hard pressed to find a laptop cheap enough to give to a grade school student. In comparison, these small electronic word processors could be purchased for as little as $150. Not only was the initial price low, but the maintenance costs were almost negligible. They ran for hundreds of hours on a standard AA batteries, and didn’t require schools to have any IT staff to manage them. Sure they couldn’t get on the Internet or even run any software, but they would give students a chance to hone their keyboarding skills. Continue reading “Teardown: The Writer Word Processor”