We’ve all heard the incredible claims made about graphene and its many promising applications, but so far the wonder-material has been held back by the difficulty of producing it in large quantities. Although small-scale production was demonstrated many years ago using basic Scotch tape, producing grams or even kilograms of it in a scalable industrial process seemed like a pipedream — until recently. As [Tech Ingredients] demonstrates in a new video, the technique of flash Joule heating of carbon may enable industrial graphene production.

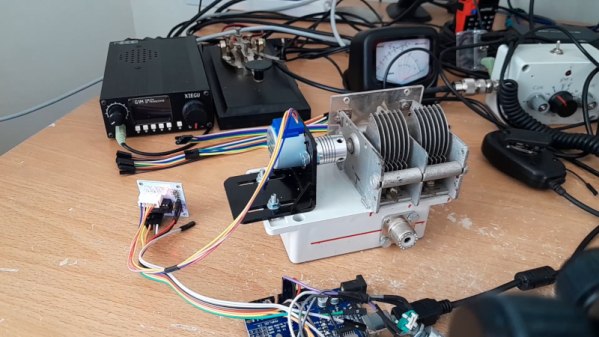

The production of this flash graphene (FG) was first demonstrated by Duy X. Luong and colleagues in a 2020 paper in Nature, which describes a fairly straightforward process. In the [Tech Ingredients] demonstration it becomes obvious how easy graphene manufacturing is using this method, requiring nothing more than carbon black as ingredient, along with a capacitor bank, vacuum chamber and a number of reasonably affordable items.

Perhaps best of all is that no refinement or other complicated processes are required to separate the produced graphene from the left-over carbon black and other non-graphene products. Using multiple of these carbon black-filled tubes in parallel, producing graphene could conceivably be scaled up to industrial levels. This would make producing a few kilograms of graphene significantly easier than coating hard drive platters with the substance.

Continue reading “The Challenges Of Producing Graphene In Quantity”