Everyone knows that the path of least resistance is the path that will always be taken, be it by water, electricity or the feet of humans. This is where the PCB presented by [ElectrArc240] on YouTube is rather confusing, as it demonstrates two similarly sized traces, one of which is much shorter than the other, yet the current opts to travel via the much longer trace. If you were to measure this PCB between each path, the shorter path has the lowest resistance at 0.44 Ω while the longer path is 1.44 Ω. Did the laws of physics break down here?

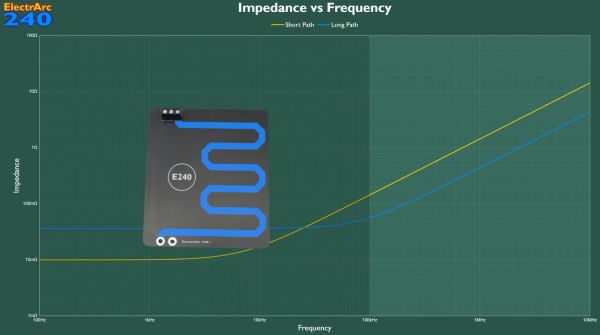

Of course, this is just a trick question, as the effective resistance for an electrical circuit isn’t just about ohmic resistance. Instead the relevant phrasing here is ‘path of least impedance‘, which is excellently demonstrated here using this PCB. Note that its return path sneaks on the back side along the same path as the long path on the front. To this is added a 1 MHz high current source that demonstrates the impact of alternating current, with reactance combining with the resistance.

Although for direct current it’s fair to say that impedance is the equivalent of resistance, once the inductance of a trace has to be taken into account – as in the case of AC and high-frequency signaling – the much higher inductance of the short path means that now the long path is actually the shortest.

When you are doing some impedance matching in your favorite EDA software while implementing an Ethernet RMII link or similar, this is basically part of the process, with higher frequencies requiring ever more stringent mechanisms to keep both sides happy. At some point any stray signals from nearby traces and components become a factor, never mind the properties of the PCB material.

Continue reading “When Electricity Doesn’t Take The Shortest Path”