One may think that when it comes to 3D printing, slicing software is pretty much a solved problem. Take a 3D model, slice it into flat layers equal to layer height, and make a toolpath so the nozzle can create those layers one at a time. However, as 3D printing becomes more complex and capable, this “flat planar slicing” approach will eventually become a limitation because a series of flat slices won’t necessarily the best way to treat all objects (nor all materials or toolheads, for that matter.)

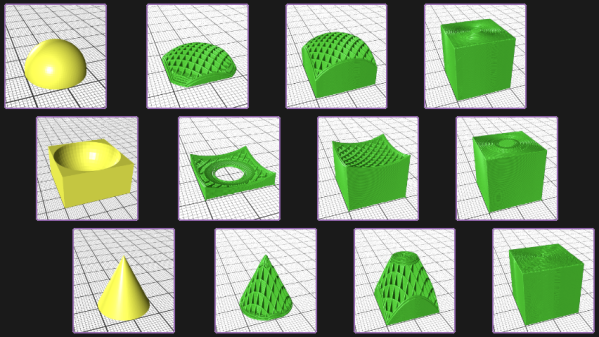

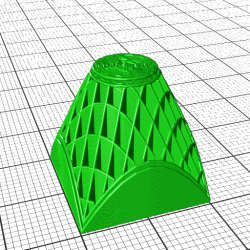

[René K. Müller] works to re-imagine slicing itself, and shows off the results of slicing 3D models using non-planar geometries. There are loads of pictures of a 20 mm cube being sliced with a variety of different geometries, so be sure to give it a look. There’s a video embedded below the page break that covers the main points.

It’s all forward-thinking stuff, and [René] certainly makes some compelling points in favor of a need for universal slicing; a system capable of handling any geometry, with the freedom to process along any path or direction. This is a concept that raises other interesting questions, too. For example, when slicing a 20 mm cube with non-planar geometries, the resulting slices often look strange. What’s the best way to create a toolpath for such a slice? After all, some slicing geometries are clearly better for the object, but can’t be accommodated by normal hot ends (that’s where a rotating, tilted nozzle comes in.)

Such worries may not be an issue for most users at the moment, but it’s worth trying to get ahead of the curve on something like this. And lest anyone think that non-planar slicing has no practical purpose, we previously covered [René]’s demonstration of how non-planar slicing can reliably create 90° overhangs with no supports.

Continue reading “A Universal, Non-planar Slicer For 3D Printing Is Worth Thinking About”