The average Hackaday user could probably piece together a rough model of a simple DC motor with what they’ve got kicking around the parts bin. We imagine some of you could even get a brushless one up and running without too much trouble. But what about an electrostatic corona motor? If your knowledge of turning high voltage into rotational energy is a bit rusty, let [Jay Bowles] show you the ropes in his latest Plasma Channel video.

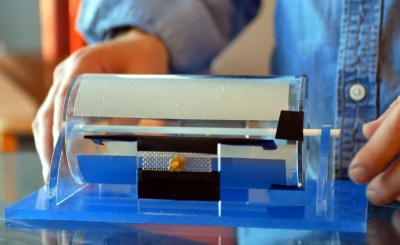

Like many of his projects, this corona motor relies on a few sheets of acrylic, a handful of fasteners, and a healthy dose of physics. The actual construction and wiring of the motor is, if you’ll excuse the pun, shockingly simple. Of course part of that is due to the fact that the motor is only half the equation, you still need a high voltage source to get it running.

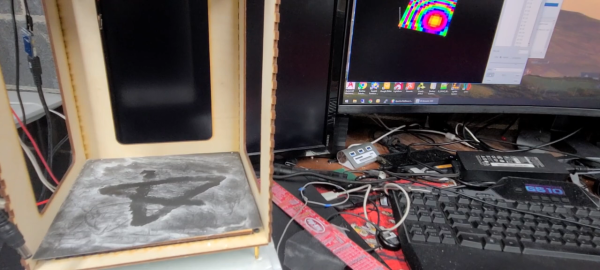

In this case, [Jay] is revisiting his earlier experiments with atmospheric electricity to provide the necessary jolt. One side of the motor is connected to a metallic mesh electrode that’s carried 100 m into the air by a DJI Mini2 drone, while the other side is hooked up to several large nails driven into the ground.

The potential between the two gets the motor spinning, and makes for an impressive demonstration, but it’s not exactly the most practical way to experiment with your new corona motor. If you’d rather get it running on the workbench, he also shows that a more traditional high voltage source like a Van de Graaff generator will do the job nicely. As an added bonus, it can even power the device wirelessly from a few feet away.

So what can you do with a corona motor? While [Jay] is quick to explain that these sort of devices aren’t exactly known for their torque, he does show that his motor is able to lift a 45 gram weight suspended from a string. That’s frankly more power than we expected, and makes us wonder if there is some quasi-practical application for this contraption. If there is we suspect it’ll be featured in a future Plasma Channel video, so stay tuned.

Continue reading “Drone And High Voltage Spin Up This DIY Corona Motor”