Parallel computing is a fair complex subject, and something many of us only have limited hands-on experience with. But breaking up tasks into smaller chunks and shuffling them around between different processors, or even entirely different computers, is arguably the future of software development. Looking to get ahead of the game, many people put together their own affordable home clusters to help them learn the ropes.

As part of his work with decentralized cryptocurrency, [Jay Doscher] recently found himself in need of a small research cluster. He determined that the Raspberry Pi 4 would give him the best bang for his buck, so he started work on a small self-contained cluster that could handle four of the single board computers. As we’ve come to expect given his existing body of work, the final result is compact, elegant, and well documented for anyone wishing to follow in his footsteps.

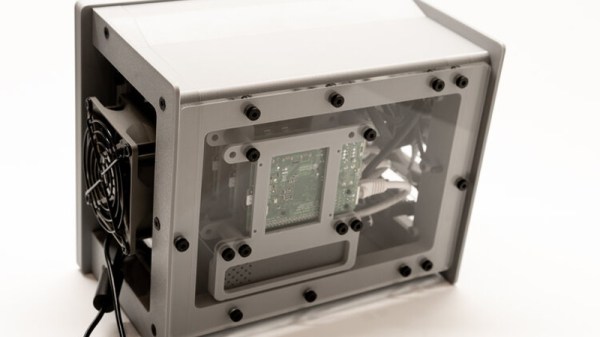

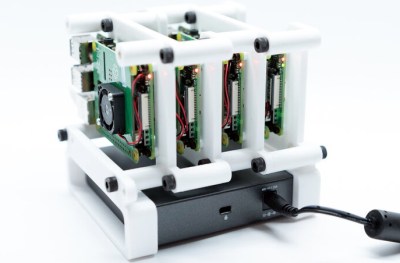

Outwardly the cluster looks quite a bit like the Mil-Plastic that he developed a few months back, complete with the same ten inch Pimoroni IPS LCD. But the internal design of the 3D printed case has been adjusted to fit four Pis with a unique staggered mounting arrangement that makes a unit considerably more compact than others we’ve seen in the past. In fact, even if you didn’t want to build the whole Cluster Deck as [Jay] calls it, just printing out the “core” itself would be a great way to put together a tidy Pi cluster for your own experimentation.

Thanks to the Power over Ethernet HAT, [Jay] only needed to run a short Ethernet cable between each Pi and the TP-Link five port switch. This largely eliminates the tangle of wires we usually associate with these little Pi clusters, which not only looks a lot cleaner, but makes it easier for the dual Noctua 80 mm to get cool air circulated inside the enclosure. Ultimately, the final product doesn’t really look like a cluster of Raspberry Pis at all. But then, we imagine that was sort of the point.

Of course, a couple of Pis and a network switch is all you really need to play around with parallel computing on everyone’s favorite Linux board. How far you take the concept after that is entirely up to you.