All of us have seen our share of phishing emails, but there are a lot more that get caught by secure email gateways and client filters. Threat actors are constantly coming up with new ways to get past these virtual gatekeepers. [BleepingComputer] investigated a new phishing attack that used some old tricks by hiding the malicious script tags as morse code.

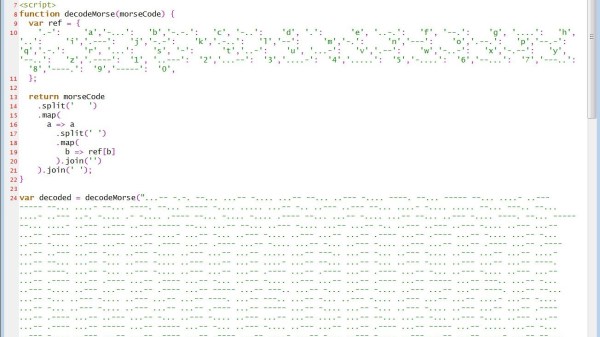

The phishing attack targets Microsoft account login credentials with an HTML page posing as an Excel invoice. When opened, it asks the user to re-enter their credentials before viewing the document. Some external scripts are required to render the fake invoice and login window but would be detected if the links were included normally. Instead, the actor encoded the script links using dots and dashes, for example, “.-” equals “a”. A simple function (creatively named “decodeMorse”) is used to decode and inject the scripts when it runs in the victim’s browser.

Of course, this sort of attack is easy to avoid with the basic precautions we are all familiar with, like not opening suspicious attachments and carefully inspecting URLs. The code used in this attack is simple enough to be used in a tutorial on JavaScript arrays, but it was good enough to slip past a few large company’s filters.

Phishing attacks are probably not going to stop anytime soon, so if you’re bored, you could go phishing for phishers, or write some scripts to flood them with fake information.