The basic 16×2 LCD is an extremely popular component that we’ve seen used in more projects than we could possibly count. Part of that is because modern microcontrollers make it so easy to work with; if you’ve got an I2C variant of the display, it only takes four wires to drive it. That puts printing a line of text on one of these LCDs a step or two above blinking an LED on a digital pin on the hierarchy of beginner’s electronics projects.

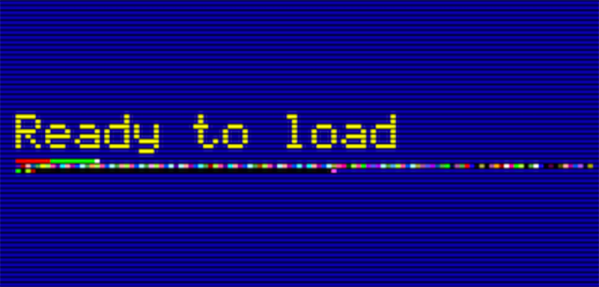

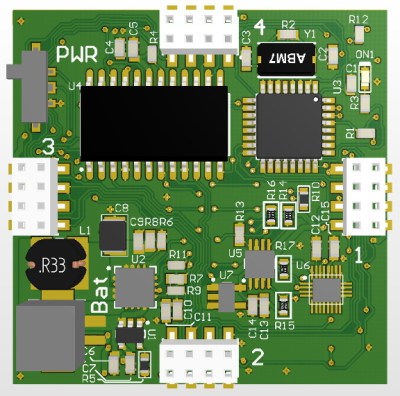

What’s that? Even four wires is too many? In that case, you might be interested in this hack from [Vinod] which shows how you can drive the classic 16×2 with data and power on the same pair of wires. You’ll still need a microcontroller “backpack” for the LCD to interpret the modulated voltage, but if you’ve got an application for a simple remote display, this is definitely worth checking out.

What’s that? Even four wires is too many? In that case, you might be interested in this hack from [Vinod] which shows how you can drive the classic 16×2 with data and power on the same pair of wires. You’ll still need a microcontroller “backpack” for the LCD to interpret the modulated voltage, but if you’ve got an application for a simple remote display, this is definitely worth checking out.

The basic idea is to “blink” the 5 V line so quick that a capacitor on the LCD side can float the electronics over the dips in voltage. As long as one of the pins of the microcontroller is connected to the 5 V line before the capacitor, it will be able to pick up when the line goes low. With a high enough data rate and a large enough capacitor as a buffer, you’re well on the way to encoding your data to be displayed.

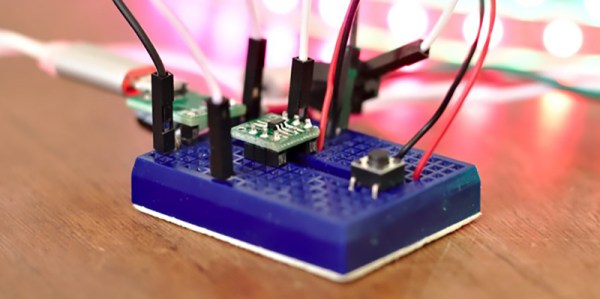

For the transmitting side, [Vinod] is using a Python script on his computer that’s sending out the text for the LCD over a standard USB to UART converter. That’s fed into a small circuit put together on a scrap of perfboard that triggers a MOSFET off of the UART TX line.

We actually covered the theory behind this technique years ago, but it’s always interesting to see somebody put together a real-world example. There might not be too many practical uses for this trick in the era of dirt-cheap microcontrollers bristling with I/O, but it might make a fun gag at your hackerspace.

Continue reading “Driving A 16×2 LCD With Voltage Modulation”