Hackaday readers are perhaps familiar with the Arduboy, an open source handheld gaming system that aims to combine the ease of Arduino development with the seething nostalgia the Internet has towards the original Nintendo Game Boy. While not quite the same as getting one of your games published for a “real” system, the open source nature of the Arduboy platform allows an individual to develop a game playable on a commercially manufactured device.

While the Arduboy hardware itself is actually quite slick, that hasn’t stopped people from trying to bring its games to other pieces of hardware. Now thanks to the efforts of [uXe], the Game Boy Advance is well on its way to becoming Arduboy compatible, in a way bringing the whole project full circle. Assuming this gadget becomes a commercial device (it sounds like that’s still up in the air), Arduboy developers will be able to proudly play their creations on the final and objectively best entry into the Game Boy line.

While the Arduboy hardware itself is actually quite slick, that hasn’t stopped people from trying to bring its games to other pieces of hardware. Now thanks to the efforts of [uXe], the Game Boy Advance is well on its way to becoming Arduboy compatible, in a way bringing the whole project full circle. Assuming this gadget becomes a commercial device (it sounds like that’s still up in the air), Arduboy developers will be able to proudly play their creations on the final and objectively best entry into the Game Boy line.

Getting to this point has been something of an adventure, as documented in a thread from the Arduboy forums. Members of the community wondered what it would take to get Arduboy games running on a real Game Boy, but pretty quickly it was decided that the original beige brick model wasn’t quite up to the task. Eventually its far more capable successor the Game Boy Advance became the development target, and different approaches were considered for getting existing games running on the platform.

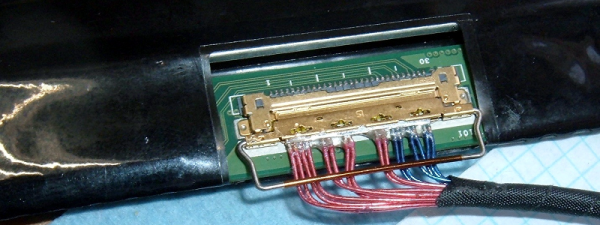

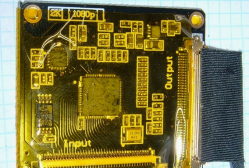

While there were some interesting ideas, such as using the GBA’s link port to “feed” the system games over SPI, in the end [uXe] decided to look into creating an FPGA cartridge that would actually run the Arduboy games. In this scenario, the GBA itself is basically just being used as an interface between the FPGA and the human player. In addition to these low-level hardware considerations, there was considerable discussion about the more practical aspects of bringing the games to the new hardware, such as how to best scale the Arduboy’s 128 x 64 output to the GBA’s 240 × 160 screen.

As demonstrated in the videos after the break, [uXe] now as all the elements for playing Arduboy games on the GBA in place, including the ability to disable full screen scaling by using the shoulder buttons. Now he just needs to shrink the hardware down to the point it will fit inside of a standard GBA cartridge. Beyond that, who knows? Perhaps the appeal of being able to run Arduboy games on a real Game Boy is enough to warrant turning this hack into a new commercial product.

Thanks to a hardware swap we’ve seen Arduboy games played on the Dreamcast VMU, and [uXe] himself previously grafted Arduboy-compatible hardware into an original Game Boy, but being able to play these games on an unmodified Game Boy Advance obviously has its own appeal. At the very least, it will be a bit more ergonomic than using a hacked classroom gadget.

Continue reading “FPGA Brings Arduboy To The Game Boy Advance” →