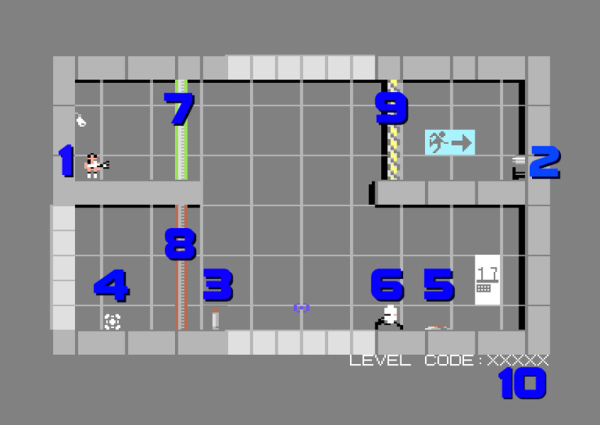

If you still have a Commodore 64 and it’s gathering dust, don’t sell it to a collector on eBay just yet. There’s still some homebrew game development happening from a small group of programmers dedicated to this classic system. The latest is a Portal-like game from [Jamie Fuller] which looks like a blast.

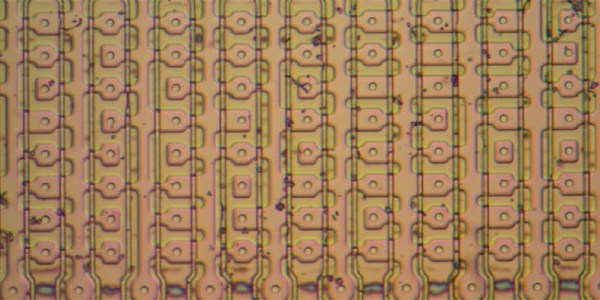

The Commodore doesn’t have quite the same specs of a Playstation, but that’s no reason to skip playing this version. It has the same style of puzzles where the player will need to shoot portals and manipulate objects in order to get to the goals. GLaDOS even makes appearances. The graphics by [Del Seymour] and music by [Roy Widding] push the hardware to its limits as well.

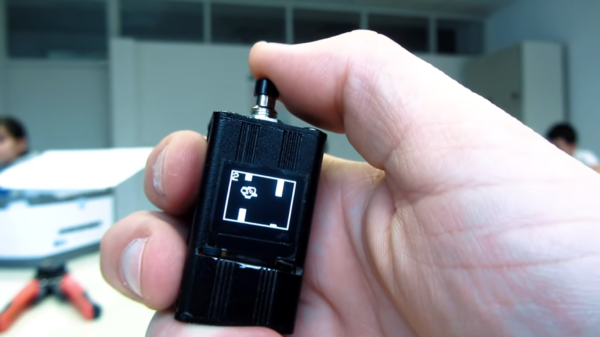

If you don’t have a C64 laying around, there are some emulators available such as VICE that can let you play this game without having to find a working computer from the 80s. You can also build your own emulator if you’re really dedicated, or restore one that had been gathering dust. And finally, we know it’s not, strictly speaking, a port of Portal, but some artistic license in headlines can be taken on occasion.

Continue reading “A Portal Port Programmed For Platforms Of The Past”