Communicating with microcontrollers and other embedded systems requires a communications standard. SPI is a great one, and is commonly used, but it’s not the only one available. There’s also I2C which has some advantages and disadvantages compared to SPI. The problem with both standards, however, is that modern computers don’t come with either built-in. To solve that problem and allow easier access to debugging in SPI, [James Bowman] built the SPIDriver a few months ago, and is now back by popular demand with a similar device for I2C, the I2CDriver.

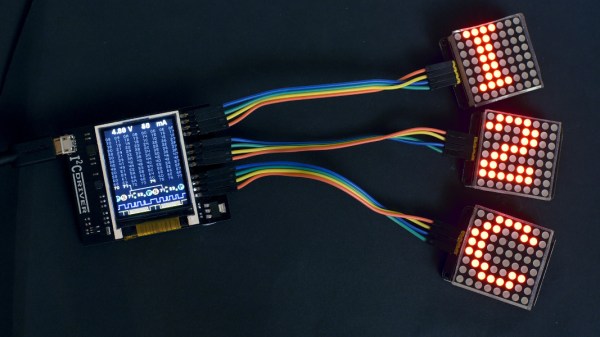

Much like the SPIDriver, the I2C driver is a debugging tool that can be used at your computer with a USB interface. Working with I2C is often a hassle, with many things going on all at once that need to sync up just right in order to work at all, and this device allows the user to set up I2C devices in a fraction of the time. To start, it has a screen built in that shows information about the current device, like the signal lines and a graphical decoding of the current traffic. It also shows an address space map, and has programmable pullup resistors built in, and can send data about the I2C traffic back to its host PC for analysis.

The I2CDriver is also completely open source, from the hardware to the software, meaning you could build one from scratch if you have the will and the parts, or make changes to the code on your own to suit your specific needs. If you’re stuck using SPI still, though, you can still find the original SPIDriver tool to help you with your debugging needs with that protocol as well.