We need to have a talk. As tough a pill as it is to swallow, we have to face that fact that some of the technology promised to us by Hollywood writers and prop makers just isn’t going to come true. We’re never going to have a flux capacitor, actual hoverboards aren’t a real thing, and nobody is going to have sword fights with laser beams.

But just because we can’t have real versions of these devices doesn’t mean we can’t make our own prop versions with a few value-added features, like this cool persistence-of-vision lightsaber. [Luni], better known around these parts as [Bitluni] and for his eponymous YouTube channel where he performs wizardry like turning an ESP32 into a software-defined television station, shows he’s no slouch at more mechanical builds either. The hardware is standard POV fare, with a gyro to sense the position of the lightsaber hilt and an ESP32 to run the long Neopixel strip in the blade. There’s also a LiPo pack and a biggish DC-DC converter; the latter contributes mightily to the look of the prop, with its large heatsinks that stick out from the end of the aluminum tubing hilt. There’s also a small speaker and amp for the requisite sound effects on startup and shutdown, and the position-sensitive thrumming is a nice touch too. Check out the POV action in the video below.

What’s that you say? You recall seeing a real lightsaber here before? Well, sort of, but that’s pushing things a bit. Or perhaps you’ve got this more destructive version in mind.

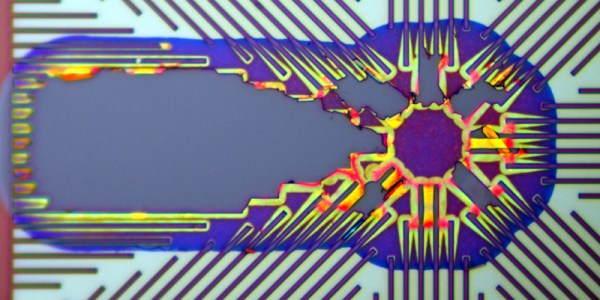

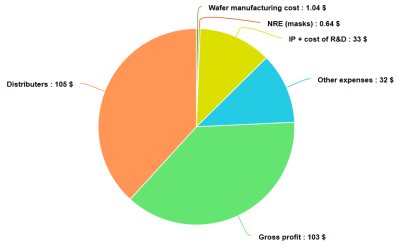

The financial analysis puts Analog Devices’s gross profit at about $103 of the $275 retail purchase price of an AD9361. The biggest slice at $105 goes to the distributor, and surprisingly the R&D and manufacturing costs are not as large as you might expect. How accurate these figures are is anybody’s guess, but they are derived from an R&D figure in the published financial report, so there is some credence to be given to them.

The financial analysis puts Analog Devices’s gross profit at about $103 of the $275 retail purchase price of an AD9361. The biggest slice at $105 goes to the distributor, and surprisingly the R&D and manufacturing costs are not as large as you might expect. How accurate these figures are is anybody’s guess, but they are derived from an R&D figure in the published financial report, so there is some credence to be given to them.