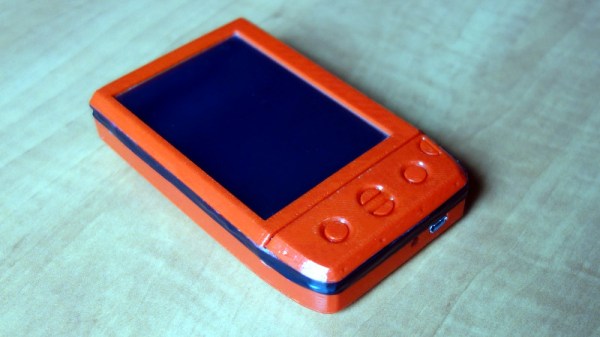

Sometimes, when you’re driving, a simple wave when someone lets you in can go unnoticed and sometimes you make a mistake and a simple wave just isn’t enough. [Noapparentfunction] came up with a nice project to say ‘Thanks’ and ‘My Bad’ to his fellow drivers.

The display uses four Max 7219 LED matrix displays, so the total resolution is 32 by 8. [Noapparentfunction] came up with an inspired idea: using a glasses case to hold the LED matrices and Raspberry Pi. It’s easy to get into if necessary, stays closed, and provides a nice finished look. Having little knowledge of electronics and no programming skills, [Noapparentfunction] had to rely on cutting and pasting Python code as well as connecting a mess of wires together, but the end result works, and that’s what matters.

A network cable runs from the glasses case suction cupped to the rear window to another project box under the dashboard. There, the network cable is connected to two buttons and the power. No network information is passed, the cable is just a convenient collection of wires with which to send signals. Each of the buttons shows a different message on the display.

Depending on where you live, this might not be legal, and we’re sure many of our readers (as well as your author) could come up with some different messages to display. However, this is a cool idea and despite [Noapparentfunction]’s admitted limitations, is a nice looking finished product. Also, its name is Road Apology Gratitude Emitter. Here are some other car mod articles: This one adds some lighting to the foot well and glove compartment and this one on the heinousness of aftermarket car alarms.

A delightful version of a clever one-dimensional game has been made by [Critters] which he calls

A delightful version of a clever one-dimensional game has been made by [Critters] which he calls