Finding the right wall wart or charger to go with an appliance might be a matter of convenience to you and I, but there are some people who really, really need the right charger, because not having it could mean a fire.

[marius] is a Romanian hardware engineer who moved to Papua New Guinea, where he had the opportunity to travel in the remote jungle of that country. There, he saw many people who used solar panels to charge car batteries for a 3W light bulb at night, their phones, or other conveniences that only need a few Watt-hours a day. Connecting car batteries directly to solar panels isn’t a smart idea, so [marius] set out to create a simple, very low-cost DC-DC voltage converter. He’s calling it the Scorpion 3.0, and it looks like a fantastic tool for low-income areas that are far off the grid.

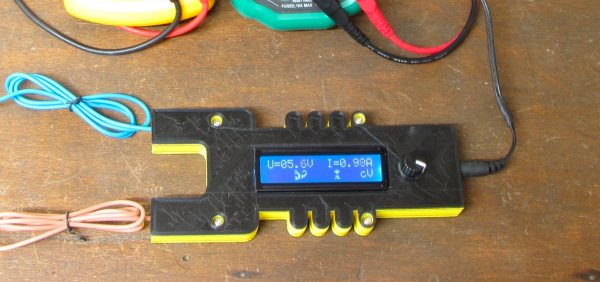

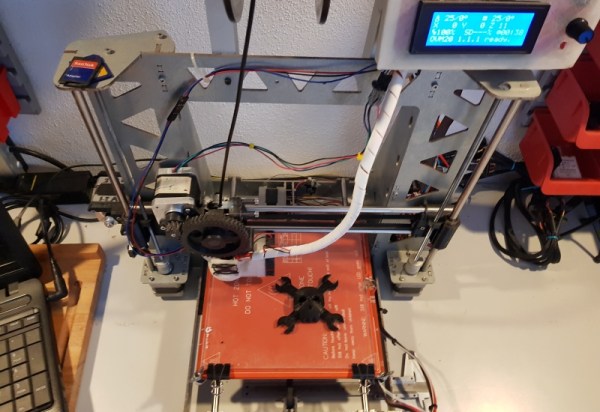

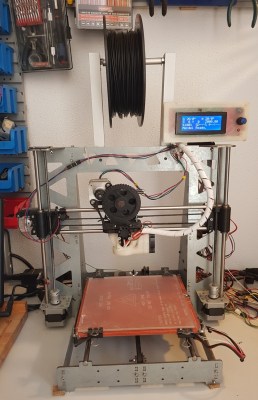

The design of the Scorpion consists of a 3D printed enclosure, with one forked end containing some alligator clip leads, and a standard barrel jack on the other. In the middle is a character display showing the input and output voltage, and a simple rotary encoder for user interaction. The circuit for the Scorpion 3.0 consists mostly of a cheap, low-power MSP430 microcontroller managing the display, encoder, and a buck converter.

Designing something for off-the-grid usage means a few engineering challenges, and being in Paupa New Guinea, there are a few environmental considerations as well. [marius] is varnishing his 3D prints. No, it’s not going to be IP68 rated, but it helps. Making the Scorpion cheap is also a big consideration, most probably resulting in the choice of the MSP430.

It’s a great project, and an excellent entry to the Hackaday Prize. You can check out the demo video of the Scorpion below.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize Entry: Scorpion DC-DC Voltage Converter”