When a friend finds her caravan’s deep-cycle battery manager has expired over the summer, and her holiday home on wheels is without its lighting and water pump, what can you do? Faced with a dead battery with a low terminal voltage in your workshop, check its electrolyte level, hook it up to a constant current supply set at a few hundred mA, and leave it for a few days to slowly bring it up before giving it a proper charge. It probably won’t help her much beyond the outing immediately in hand, but it’s better than nothing.

A lot of us will own a lead-acid battery in our cars without ever giving it much thought. The alternator keeps it topped up, and every few years it needs replacing. Just another consumable, like tyres or brake pads. But there’s a bit more to these cells than that, and a bit of care and reading around the subject can both extend their lives in use and help bring back some of them after they have to all intents and purposes expired.

One problem in particular is sulphation of the lead plates, the build-up of insoluble lead sulphate on them which increases the internal resistance and efficiency of the cell to the point at which it becomes unusable. The sulphate can be removed with a high voltage, but at the expense of a dangerous time with a boiling battery spewing sulphuric acid and lead salts. The solution therefore proposed is to pulse it with higher voltage spikes over and above charging at its healthy voltage, thus providing the extra kick required to shift the sulphation build up without boiling the electrolyte.

If you read around the web, there are numerous miracle cures for lead-acid batteries to be found. Some suggest adding epsom salts, others alum, and there are even people who talk about reversing the charge polarity for a while (but not in a Star Trek sense, sadly). You can even buy commercial products, little tablets that you drop in the top of each cell. The problem is, they all have the air of those YouTube videos promising miracle free energy from magnets about them, long on promise and short on credible demonstrations. Our skeptic radar pings when people bring resonances into discussions like these.

So so these pulse desulphators work? Have you built one, and did it bring back your battery from the dead? Or are they snake oil? We’ve featured one before here, but sadly the web link it points to is now only available via the Wayback Machine.

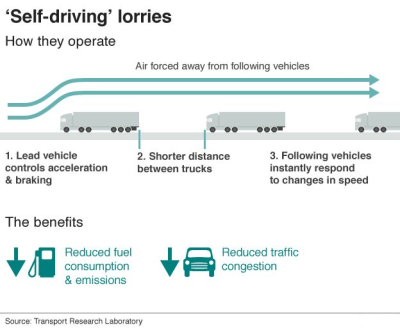

will connect to the others wirelessly and control their braking and acceleration. Human drivers will still be present to steer the following lorries in the convoy.

will connect to the others wirelessly and control their braking and acceleration. Human drivers will still be present to steer the following lorries in the convoy.