You hear about people finding USB drives and popping them into a computer to see what’s on them, only to end up loading some sort of malware onto their computer. It got me to thinking, given this notorious vulnerability, is it really a great idea to make electronics projects that plug into a computer’s USB port? Should I really contribute to the capitulation-by-ubiquity that USB has become?

A of couple years ago I was working on an innocuous project, a LED status light running off of USB. It ran off USB because I had more complicated hopes for it–some vague notion about some kind of notification thing and also it was cool to have access to 5 V right from the ‘puter. This was about the time that those little RGB LEDs connected to USB were all the rage, like blink(1), which raised $130,000 on Kickstarter. I just wanted to make a status light of some sort and had the parts, so I made it.

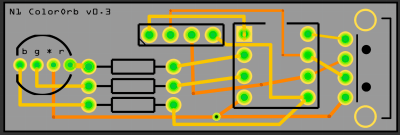

My version was a small rectangular PCB from OSHPark packing a Tiny85, with a 10 mm RGB LED providing pretty much all of the functionality — no spare pins broken out. Honestly, for the amount of code on it, even the Tiny85 was overpowered. I recall thinking at the time, could my creation be misused for evil? Could some wicked programmer include malware alongside my LED-lighting Arduino sketch?

My version was a small rectangular PCB from OSHPark packing a Tiny85, with a 10 mm RGB LED providing pretty much all of the functionality — no spare pins broken out. Honestly, for the amount of code on it, even the Tiny85 was overpowered. I recall thinking at the time, could my creation be misused for evil? Could some wicked programmer include malware alongside my LED-lighting Arduino sketch?

It’s absurd, of course. My meager engineering skills ought not interest anyone. On the other hand, couldn’t some heartless poltroon, the hardware equivalent of a script kiddie, make my creation into a malware-spewing Typhoid Mary of a project? It has always been the realistic consequence of building anything–that it could be misused. I’d be thrilled to the point of giddiness if someone remade one of my projects into something cool, but I’d really hate for a USB light I designed to turn into some vector into someone’s computer. But how much of that is my responsibility?

If you think I’m the only one who thinks this, go to SparkFun or Adafruit and count all of the boards with microcontrollers and USB A male plugs. Even the tiny boards like the Huzzah and Gemma use USB cables, rather than plugging directly into the computer. Granted, they are microcontrollers that realistically would be connected to a project and it might not be possible to physically move them into position and plug them in. Also requiring a charging cable does not in any way make a microcontroller board work any differently than one plugged right into the computer. I’m left wondering if I’m spazzing out over nothing, and there’s nothing we can do about our tendency to treat any electronic gizmo with a shiny case as being safe to plug into the same computer we use to pay bills.

If there is no data transfer taking place, and I’m just getting power, wouldn’t it be enough to disable (or not connect) the data pins of the USB on the circuit board? Or maybe we really have no business connecting a data connection to a microcontroller if we’re not reflashing the chip with fresh code–think I’m paranoid? Maybe you should just get power from a wall wart and leave the USB cord in the drawer. It’s one thing to urge our friends and family to steer clear of mystery plugs, but as engineers and tinkerers, do we not owe the community the benefit of our knowledge?

Of course, Hackaday contains numerous examples of USB projects, including canary for USB ports, tips on protecting your ports with two microcontrollers, a guide to stopping rubber ducky attacks, and removing security issues from untrusted USB connections. Also, has anyone used the USB condom?

Friends, let me know your thoughts on the subject. Am I a freak to steer clear of USB-powered project like my dumb LED? Leave your comments and weigh in with your opinions.