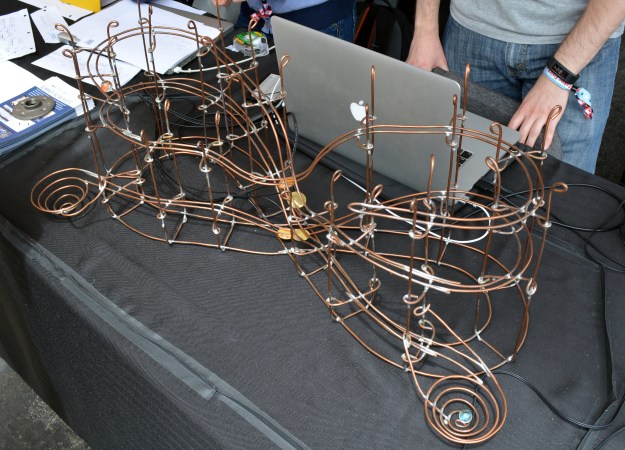

Building a marble run has long been on my project list, but now I’m going to have to revise that plan. In addition to building an interesting track for the orbs to traverse, [Jack Atherton] added custom sound effects triggered by the marble.

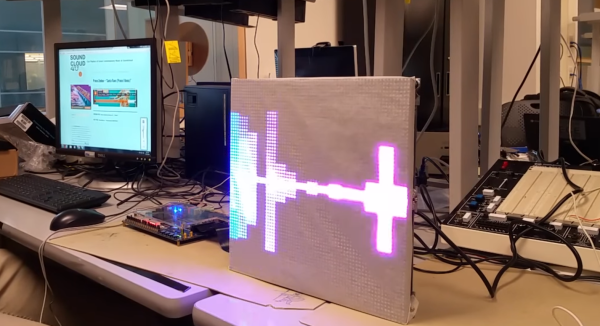

I ran into [Jack] at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics booth at Maker Faire. That’s a mouthful, so they usually go with the acronym CCRMA. In addition to his project there were numerous others on display and all have a brief write-up for your enjoyment.

[Jack] calls his project Leap the Dips which is the same name as the roller coaster the track was modeled after. This is the first I’ve heard of laying out a rolling ball sculpture track by following an amusement park ride, but it makes a lot of sense since the engineering for keeping the ball rolling has already been done. After bending the heavy gauge wire [Jack] secured it in place with lead-free solder and a blowtorch.

As mentioned, the project didn’t stop there. He added four piezo elements which are monitored by an Arduino board. Each is at a particularly extreme dip in the track which makes it easy to detect the marble rolling past. The USB connection to the computer allows the Arduino to trigger a MaxMSP patch to play back the sound effects.

For the demonstration, Faire goers wear headphones while letting the balls roll, but in the video below [Jack] let me plug in directly to the headphone port on his Macbook. It’s a bit weird, since there no background sound of the Faire during this part, but it was the only way I could get a reasonable recording of the audio. I love the effect, and think it would be really fun packaging this as a standalone using the Teensy Audio library and audio adapter hardware.