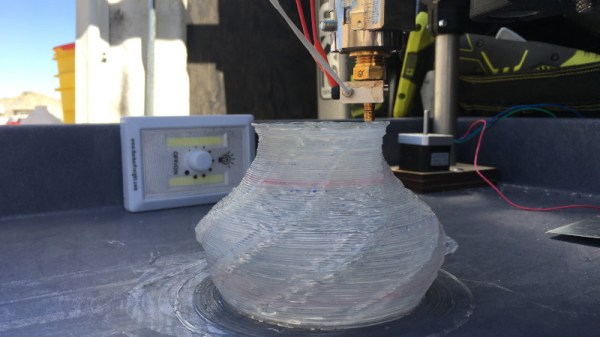

It’s been just over a year since E3D whetted our appetites for toolchanging printers. Now, with the impending release of their first toolchanging system, they’ve taken the best parts of their design and released them into the wild as open source. Head on over to Github for a complete solution to exchanging, locating, and parking tools on a 3D printer.

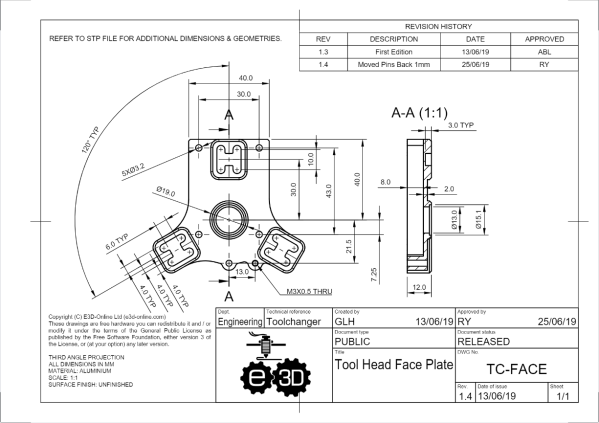

For anyone interested in fabricating the design, the files are in a format that you can almost re-zip and email to a manufacturer for quotes. As is, the repository offers STP-style CAD files, a complete set of dimensioned drawings, exploded views, and even a bill of materials. Taken as a whole, the system elegantly solves the classic problems that we’d encounter in toolchanging. Locking tools is done with a spring-based T-bar that swivels onto an wedge-shaped groove on the back of each tool plate. Locating tools is done so with a 3-groove kinematic coupling fabriacted from dowel pins. With these problems solved and presented so cleanly, these files become a path by which we can establish a common means for exchanging tools on 3D printer systems.

It’s worth asking: why develop an exceptional design and then release it for free? I’ll speculate that E3D has done an excellent job over the years establishing a well-recognized standard set of stock parts. Nearly every 3D printer builder is bound to have at least one spare V6 hotend sitting idle in a disassembled pool of former-3D-printers. With tool-changing positioned to become another step forward in the space of possibilities with 3D printing, setting the standard for tools early encourages the community to continue developing applications that lean on E3D’s ecosystem of parts.

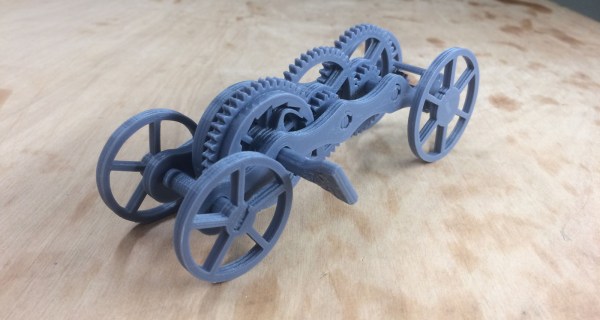

In the last 30 years, 3D printing has transformed away from a patent-trolling duopoly to a community-friendly group of contributors that lean on each other’s shoulders with shared findings. It’s a kind gesture to the open-source community of machine builders to receive such a feature-complete mechanism. With that said, let’s start rolling the toolchanger hacks.