Modern handheld gaming hardware is great. The units are ergonomic powerhouses, yet many of us do all our portable gaming on a painfully rectangular smartphone. Their primary method of interaction is the index finger or thumbs, not a D-pad and buttons. Shoulder triggers have only existed on a few phones. Bluetooth gaming pads are affordable but they are either bulky or you have to find another way to hold your phone. Detachable shoulder buttons are a perfect compromise since they can fit in a coin purse and they’re cheap because you can make your own.

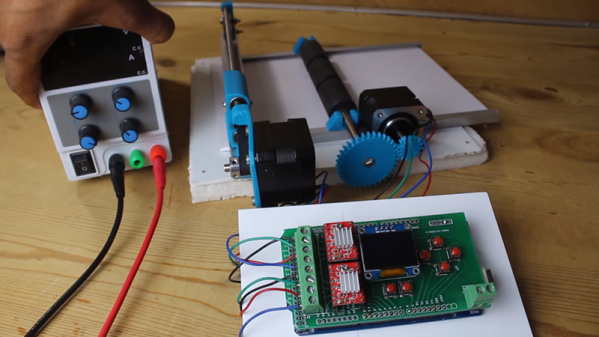

[ASCAS] explains how his levers work to translate a physical lever press into a capacitive touch response. The basic premise is that the contact point is always touching the screen, but until you pull the lever, which is covered in aluminum tape, the screen won’t sense anything there. It’s pretty clever, and the whole kit can be built with consumables usually stocked in hardware stores and hacker basements and it should work on any capacitive touch screen.

Physical buttons and phones don’t have to be estranged and full-fledged keyswitches aren’t exempt. Or maybe many capacitive touch switches are your forte.

Continue reading “Print Physical Buttons For Your Touch Screen”