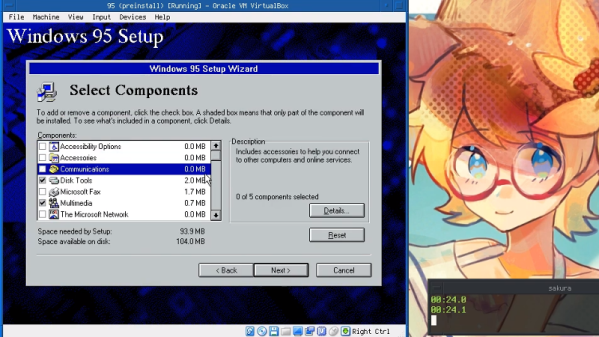

Speedrunning is the practice of attempting to beat a videogame in as short a time as possible. There are a huge variety of methods and styles. There are 100% completion speedruns, tool-assisted speedruns, and speedruns that just focus on getting to the game over screen as quickly as possible by hook or by crook. Now, there’s a world record speedrun, installing Windows 95B in just 1 minute 10.9 seconds.

The current best attempts are collected in a Google Sheets document. So far, there have been few competitors but we expect to see more activity in future. The current rules for world record competition require original floppy and CD-ROM images to be used, but there are no limits on hardware, so records should tumble as time goes on. All the top times have been completed in virtual machines, but we’d love to see an attempt made on raw hardware.

It all kicked off when [oscareczek] grew tired of trying to compete in traditional gaming speedruns, so invented a new category instead. Competition has already come a long way from that original 4 minute time, and competitors are now considering advanced techniques such as RAM disks to speed their runs. All keystrokes are by hand at the moment, but we could see a tool-assisted competition starting up in future.

We’ve seen speedrunning techniques pushed to impressive limits before – like running Pong within Super Mario World, just for fun. Video after the break.