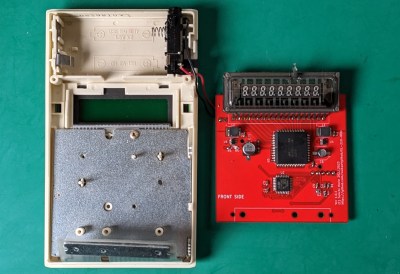

In the era of the smartphone, an electronic calculator may seem a bit old-hat. But they continue to hold a fascination in our community, both when used for their original purpose, and as objects for hardware hacking in their own right. After their first few years when they were a rare and exclusive gadget, they were manufactured in such huge numbers as to be readily available for the curious hacker. [Suikan] has taken one of these plentiful models and done something special for it, creating a new mainboard, and a firmware which transforms it into a reverse Polish, or RPN, scientific calculator.

The Sharp EL210 and EL215 were ubiquitous early-1980s calculators without scientific functions, and with a VFD display. We remember them being common during our schooldays, and they and similar models can still be found on a trawl through thrift stores.

The Sharp EL210 and EL215 were ubiquitous early-1980s calculators without scientific functions, and with a VFD display. We remember them being common during our schooldays, and they and similar models can still be found on a trawl through thrift stores.

On the board is one of the STM32 microcontrollers and a Maxim VFD driver, and fitting it is simply a case of soldering the Sharp’s VFD to it, placing it in the calculator, and attaching the keyboard. The firmware meanwhile uses the orange C key from the original calculator as a function key, alternating between standard and scientific operations.

If you’re curious about RPN, we’ve taken a look at it here in the past.