The first optical mice had to be used on a specially printed mousepad with a printed grid that the four-quadrant infrared sensor could detect. Later, mice swapped the infrared sensor for an optoelectric module (essentially a tiny, very low-resolution camera) and a powerful image processing. [8051enthusiast] was lying in bed one day when they decided to crack the firmware in their gaming mouse and eventually start streaming frames from the camera inside.

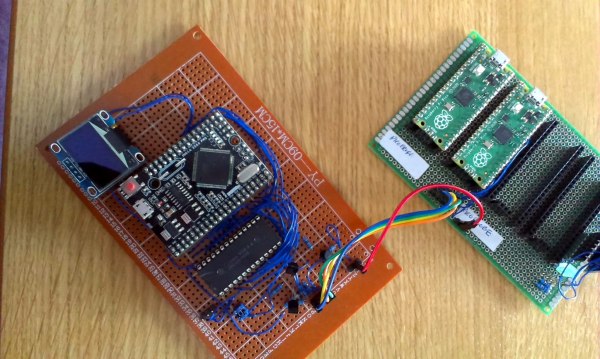

Step one was to analyze the protocol between the mouse and the host machine. Booting up a Windows VM and Wireshark allowed him to capture all the control transfers to the USB controller. Since it was a “programmable” gaming mouse that allowed a user to set macros, [8051enthusiast] could use the control transfers that would normally query that macro that had been set to return the memory at an arbitrary location. A little bit of tinkering later, and he now had a dump of the firmware. Looking at the most abundant bytes, it seems to match a profile similar to the Intel 8051. In a fascinating blur of reverse engineering, he traced the main structure of the program back from the function that sets the LED colors for the scroll wheel (which is dependent on the current DPI setting). Unfortunately, the firmware prevented the same macro mechanism from writing to arbitrary locations.

Looking through the code, a good old buffer overflow exploit seemed possible, but it caused the system to reset via watchdog. So he took another approach, invoking recovery mode and loading an entirely new firmware on the device, which a set_report control transfer can invoke.

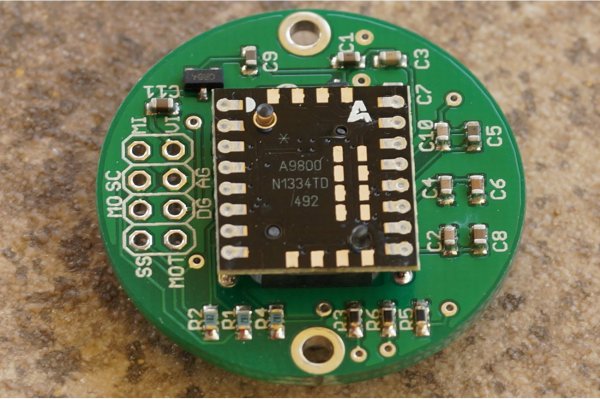

Next, he moved onto the ADNS-9800 optical sensor (pictured in the top image provided by JACK Enterprises), which had a large encrypted blob in the firmware. Some poking around and deduction lead to a guess that the optical sensor was another 8051 system. With some clever reasoning and sheer determination, [8051enthusiast] was able to crack the XOR stream cipher encryption with a program that showed him versions of the disassembled assembly and allowed him to pick the one that was the most likely. With the firmware decrypted, he was able to see the encryption code and confirm his deducted algorithm.

With the sensor now cracked open, it was onto the 30 x 30 240 fps video stream. The sensor communicates over SPI, and the USB controller has to bit-bang the connection as it doesn’t have the hardware. Putting two custom firmware images on with a few extra functions was easy enough, but the 7 fps was somewhat lacking. The first optimization was loop unrolling and removing some sleeps in the firmware, which bought it up to 34 fps. By measuring the cycle counts of individual instructions, he was able to find some alternatives such as a mov instead of a setb that took one less cycle. Going from a 17 cycle loop to an 11 cycle loop and some other optimizations gave him 54 fps. Not content to stop there, he modified the ADNS-9800 firmware to continuously sample rather than waiting for the USB controller to finish processing. While this yielded 100 fps, there was still more to do: image compression. At a whopping 230 fps, [8051enthusiast] decided to call it done.

However, there was one last thing he wanted to do: control the mouse with the video stream. Writing some image processing into his Python-based program that received the image files allowed him to use the mouse, however impractically.

All in all, it’s an incredible journey by [8051enthusiast], and we would highly recommend reading the whole journey yourself. This isn’t the first time he’s modified the firmware of 8051-based devices, such as modifying the firmware of the WiFi chipset in his laptop.

[Thanks to JACK Enterprises over at Tindie for the use of the image of an ADNS9000].