What I particularly like about the Van de Graaff (or VDG) is that it’s a combination of a few discrete scientific principles and some mechanically produced current, making it an interesting study. For example, did you know that its voltage is limited mostly by the diameter and curvature of the dome? That’s why a handheld one is harmless but you want to avoid getting zapped by one with a 15″ diameter dome. What follows is a journey through the workings of this interesting high voltage generator.

Engineering593 Articles

How Energy Gets Where Its Needed

Even if you’re reading this on a piece of paper that was hand-delivered to you in the Siberian wilderness, somewhere someone had to use energy to run a printer and also had to somehow get all of this information from the energy-consuming information superhighway. While we rely on the electric grid for a lot of our daily energy needs like these, it’s often unclear exactly how the energy from nuclear fuel rods, fossil fuels, or wind and solar gets turned into electrons that somehow get into the things that need those electrons. We covered a little bit about the history of the electric grid and how it came to be in the first of this series of posts, but how exactly does energy get delivered to us over the grid? Continue reading “How Energy Gets Where Its Needed”

Taking The Leap Off Board: An Introduction To I2C Over Long Wires

If you’re reading these pages, odds are good that you’ve worked with I²C devices before. You might even be the proud owner of a couple dozen sensors pre-loaded on breakout boards, ready for breadboarding with their pins exposed. With vendors like Sparkfun and Adafruit popping I²C devices onto cute breakout boards, it’s tempting to finish off a project with the same hookup wires we started it with.

It’s also easy to start thinking we could even make those wires longer — long enough to wire down my forearm, my robot chassis, or some other container for remote sensing. (Guilty!) In fact, with all the build logs publishing marvelous sensor “Christmas-trees” sprawling out of a breadboard, it’s easy to forget that I²C signals were never meant to run down any length of cable to begin with!

As I learned quickly at my first job, for industry-grade (and pretty much any other rugged) projects out there, running unprotected SPI or I²C signals down any form of lengthy cable introduces the chance for all sorts of glitches along the way.

I thought I’d take this week to break down that misconception of running I²C over cables, and then give a couple examples on “how to do it right.”

Heads-up: if you’re just diving into I²C, let our very own [Elliot] take you on a crash course. Continue reading “Taking The Leap Off Board: An Introduction To I2C Over Long Wires”

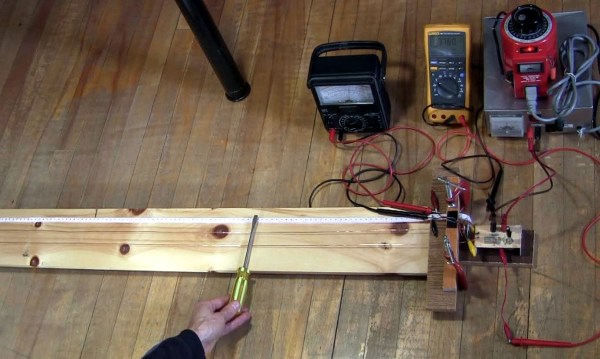

Using A Lecher Line To Measure High Frequency

How do you test the oscillator circuit you just made that runs between 200MHz and 380MHz if all you have is a 100MHz oscilloscope, a few multimeters and a DC power supply? One answer is to put away the oscilloscope and use the rest along with a length of wire instead. Form the wire into a Lecher line.

That’s just what I did when I wanted to test my oscillator circuit based around the Mini-Circuits POS-400+ voltage controlled oscillator chip (PDF). I wasn’t going for precision, just verification that the chip works and that my circuit can adjust the frequency. And as you’ll see below, I got a fairly linear graph relating the control voltages to different frequencies.

What follows is a bit about Lecher lines, how I did it, and the results.

Continue reading “Using A Lecher Line To Measure High Frequency”

Hacking The Aether: How Data Crosses The Air-Gap

It is incredibly interesting how many parts of a computer system are capable of leaking data in ways that is hard to imagine. Part of securing highly sensitive locations involves securing the computers and networks used in those facilities in order to prevent this. These IT security policies and practices have been evolving and tightening through the years, as malicious actors increasingly target vital infrastructure.

Sometimes, when implementing strong security measures on a vital computer system, a technique called air-gapping is used. Air-gapping is a measure or set of measures to ensure a secure computer is physically isolated from unsecured networks, such as the public Internet or an unsecured local area network. Sometimes it’s just ensuring the computer is off the Internet. But it may mean completely isolating for the computer: removing WiFi cards, cameras, microphones, speakers, CD-ROM drives, USB ports, or whatever can be used to exchange data. In this article I will dive into air-gapped computers, air-gap covert channels, and how attackers might be able to exfiltrate information from such isolated systems.

Continue reading “Hacking The Aether: How Data Crosses The Air-Gap”

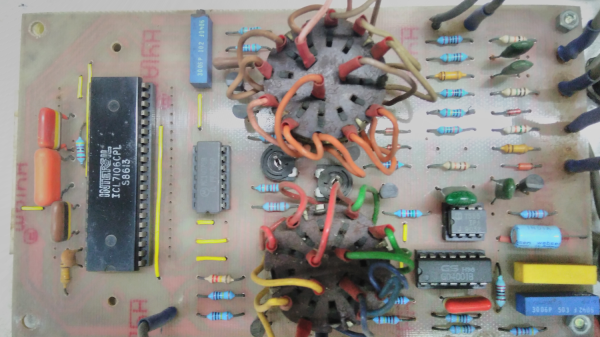

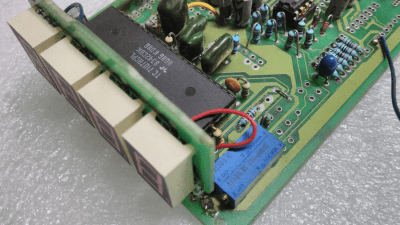

Get To Know 3½ Digit ADCs With The ICL71xx

Riffling through my box of old projects, I came upon a project that I had built in the 80’s — an Automotive Multimeter which was published in the Dutch/British Elektor magazine. It could measure low voltage DC, high current DC, resistance, dwell angle, and engine RPM and ran off a single 9V battery. Besides a 555 IC for the dwell and RPM measurement and a couple of CMOS gate chips, the rest of the board is populated by a smattering of passives and a big, 40 pin DIP IC under the 3½ digit LCD display. I dug some more in my box, and came up with another Elektor project from back then — a True RMS digital Wattmeter with a 3½ digit LCD display that could measure up to 2kW. It had the same chip too. Some more digging, and I found a digital panel meter. This had a 7 segment LED display, but the chip was again from the same family.

Look under the hood of any device with a 3½ or 4½ digit, 7 segment, LCD or LED from the ’80’s or ’90’s and you will likely spot this 40-pin DIP with the Intersil logo (although it was later also manufactured by many other fabs; Harris and Maxim among others). The chip doing all the heavy-lifting was likely to be the ICL7106 or ICL7107. These devices were described as high performance, low power, 3½ digit A/D converters containing seven segment decoders, display drivers, voltage reference and clock. In short, everything you needed to take a DC analog signal and display it. Over time, a whole series of devices were spawned:

- 7106 – 3½ digit, 7 segment LCD

- 7107 – 3½ digit, 7 segment LED

- 7116 – 3½ digit, 7 segment LCD, with display HOLD (freeze)

- 7117 – 3½ digit, 7 segment LED, with display HOLD (freeze)

- 7126 – improved 7106

- 7136 – improved 7126

- 7135 – 4½ digit, 7 segment LCD

There were many similar devices available, but the ICL71xx series was by far one of the most popular, due to its easy of use, low parts count and single chip implementation. Here are several parts (linking to PDF datasheets) to illustrate my point: the TC14433/A needed several peripheral devices, ES5107 (a clone of a clone — read below), CA3162 (which has BCD output, and needs the CA3161 or similar to interface to a display), or the AD2020 (which too needed a lot of support circuitry).

The ICL71xx was the go-to device for a reason. Let’s take a look at the engineering and business behind this fascinating chip.

Continue reading “Get To Know 3½ Digit ADCs With The ICL71xx”

PCB Design Guidelines To Minimize RF Transmissions

There are certain design guidelines for PCBs that don’t make a lot of sense, and practices that seem excessive and unnecessary. Often these are motivated by the black magic that is RF transmission. This is either an unfortunate and unintended consequence of electronic circuits, or a magical and useful feature of them, and a lot of design time goes into reducing or removing these effects or tuning them.

You’re wondering how important this is for your projects and whether you should worry about unintentional radiated emissions. On the Baddeley scale of importance:

- Pffffft – You’re building a one-off project that uses battery power and a single microcontroller with a few GPIO. Basically all your Arduino projects and around-the-house fun.

- Meh – You’re building a one-off that plugs into a wall or has an intentional radio on board — a run-of-the-mill IoT thingamajig. Or you’re selling a product that is battery powered but doesn’t intentionally transmit anything.

- Yeeeaaaaahhhhhhh – You’re selling a product that is wall powered.

- YES – You’re selling a product that is an intentional transmitter, or has a lot of fast signals, or is manufactured in large volumes.

- SMH – You’re the manufacturer of a neon sign that is taking out all wireless signals within a few blocks.

Continue reading “PCB Design Guidelines To Minimize RF Transmissions”