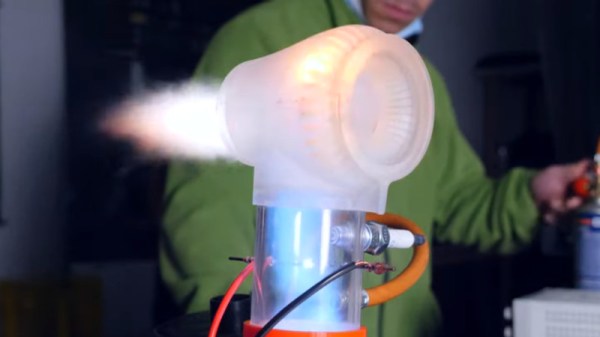

Many readers will be familiar with the Dyson Air Multiplier, an ingenious bladeless fan design in which a compressor pushes jets of air from the inside edge of a large ring. This fast-moving air draws the surrounding air through the ring, giving the effect of a large conventional fan without any visible moving parts and in a small package. It’s left to [Integza] to take this idea and see it as the compressor for a jet engine, and though the prototype you see in the video below is fragile and prone to melting, it shows some promise.

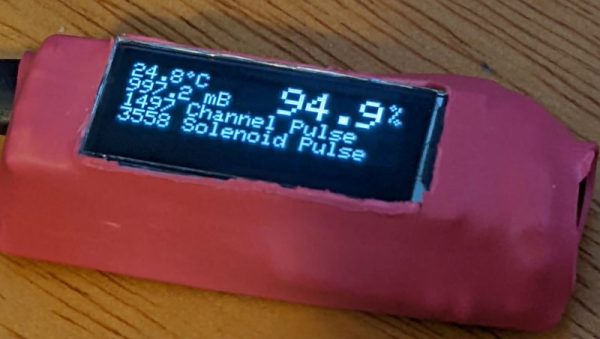

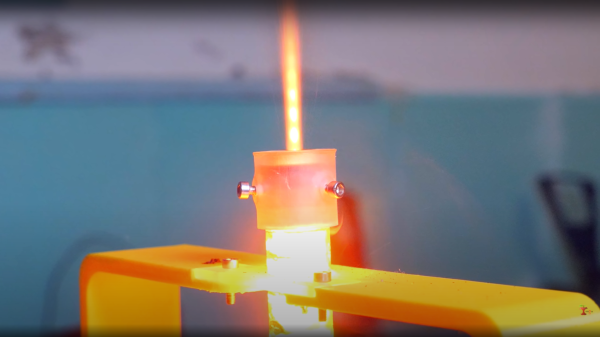

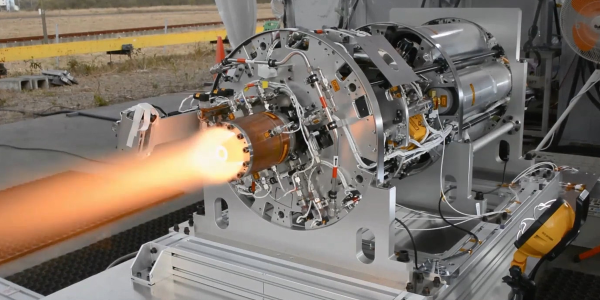

His design copies the layout of a Dyson with the compressor underneath the ring, with a gas injector and igniter immediately above it. The burning gas-air mixture passes through the jets and draws the extra air through the ring, eventually forming a roaring jet engine flame exhaust behind it. Unfortunately the choice of 3D print for the prototype leads to very short run times before melting, but it’s possible to see it working during that brief window. Future work will involve a non-combustible construction, but his early efforts were unsatisfactory.

It’s clear that he hasn’t created the equivalent of a conventional turbojet. Since it appears that its operation happens when the flame has passed into the center of the ring, it has more in common with a ramjet that gains its required air velocity with the help of extra energy from an external compressor. Whether he’s created an interesting toy or a useful idea remains to be answered, but it’s certainly an entertaining video to watch.

Meanwhile, this isn’t the first project we’ve seen inspired by the Air Multiplier.

Continue reading “The Air Multiplier Fan Principle, Applied To A Jet Engine”