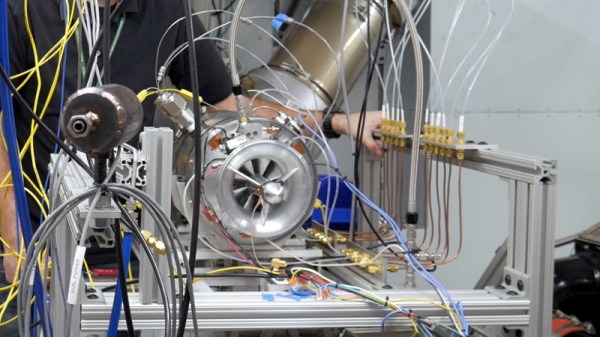

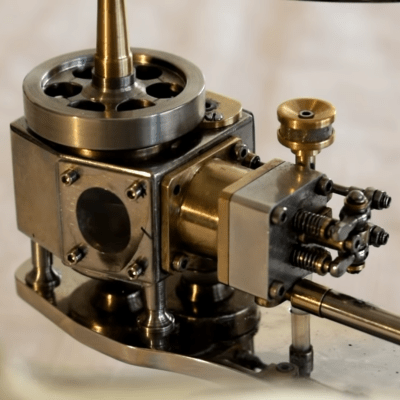

From time to time it’s good to be reminded that mechanical engineering can also be art. [José Manuel Hermo Barreiro], also known as [Patelo], is a retired naval mechanic with a love for scale model engines. Using only basic tools and a lathe, he has built a non-flying hexacopter display model, each propeller turned by a tiny single cylinder motor that runs on compressed air. From the tiny components of the valve systems, the brass framed acrylic windows into the crankcases, and the persistence of vision disc on the exhaust, the attention to detail is breathtaking.

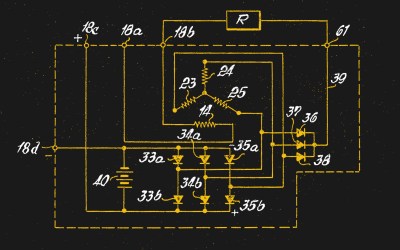

[Patelo] started the project on paper, and created a set of detailed hand-drawn blueprints to work from. Sadly a large part of the build took place during lockdown, and was not filmed, but we still get to see some work on a crankcase, connecting rod, camshaft, propellers, flywheel, and exhaust tubes. It is very clear that [Patelo] knows his way around his lathe very well, and is very creative with custom tools and jigs. The beautiful machine took approximately 1,560 hours to build, consists of 265 individually made parts held together with 362 screws.

We previously featured tiny V-12 engine that [Patelo] built around 2012. At that time he was 72 years of age, which means he should be around 80 now. We can only hope to come to emulate him one day, and that we get to see more of what comes out of his workshop. Hats off to you, sir.