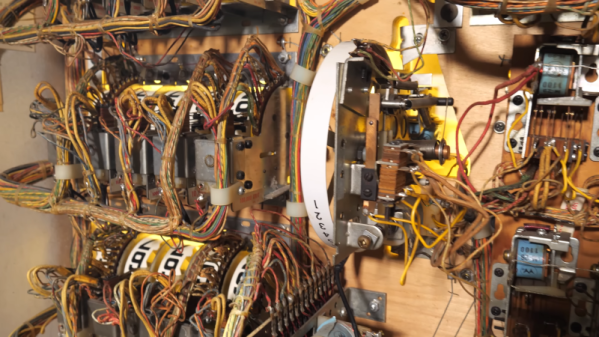

Pinball machines were the video games of their day. Back when they were king, there were no microcontrollers — everything was electromechanical. We know from experience that fixing these was difficult but we imagine that designing complex play behavior with a bunch of motors, relays, clutches, contacts, and more would have been excruciatingly difficult. [Technology Connections] has several videos about an old Aztec machine and he promises more to come. You can watch the first two below.

To give you an idea of what’s involved, imagine a very simple pinball machine that supports a single player and a handful of targets. When the ball hits a target, that could trigger a micro-switch. The switch closure could trigger a relay that closes a contact for a short period of time. That contact energizes a solenoid that advances the score wheels. So now, when a ball hits a target, the score wheel will spin enough to award ten points. To make sure there is enough time for the score to advance, the relay uses something like a mechanical flip flop.

Sound complicated? That’s nothing. Don’t forget, the machine also has to reset the score at the start of the game, count the ball in play, and end the game when the last ball returns. Then consider a real game. There will be multiple players and fancy sequences (e.g., hit the red target three times to award double scores for other targets).

While we knew a fair bit about the design of pinball machines already, we did learn a lot about their history and where the idea came from. The video also explains why it is called pinball since modern machines don’t really have pins — these were like relay-based computers with strange electromagnetic I/O devices.

While pinball machines were the best example of this sort of thing, there were also things like bowling machines and ladder-logic industrial control systems. We’ve even seen an electromechanical phone answering machine.