[JC Sheitan Tenet] lost his right arm when he was 10 years old. As most of us, he was right-handed, so the challenges he had to face by not having an arm become even harder.

Have you ever tried to perform mundane tasks with your non-dominant hand? If you’re right-handed, have you ever tried to feed yourself with your left? Or if you’re left-handed, how well can you write with your right? For some people, using both hands comes naturally, but if you’re anything like me, your non-dominant hand is just about useless.

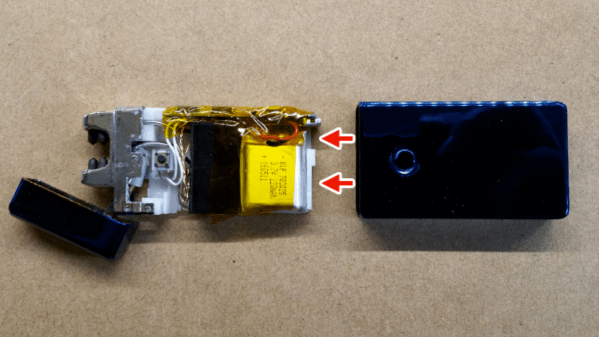

The thing is, he wanted to be a tattoo artist. And he wasn’t giving up. Even facing the added difficulty of not finding a tattoo artist that wanted to take him as an apprentice, he did not gave up. So he became a tattoo artist, using only his left arm. That is, until some months ago, when he met [Jean-Louis Gonzal], a bio-mechanical artist with an engineer background, at a tattoo convention. After seeing [Gonzal] work, he just asked if it was possible to modify a prosthesis and attach a tattoo machine to it.

The Cyborg Artist is born. The tattoo machine in the prosthesis can move 360 degrees for a wide range of movements. [JC Sheitan Tenet] uses it to help with colours, shadows and abstract forms in general. It’s a bad-ass steam punk prosthesis and it’s not just for show, he actually works with it (although not exclusively) . This, it seems, is only the beginning, since the first version of prototype worked so well, the second version is already being planned by [JC] and [Gonzal]. We can’t wait to see what they’ll come up with, maybe a mix between current version and a tattoo robotic arm or a brain controlled needle?

Check it out in the video:

Continue reading “The Cyborg Artist – Tattoo Machine Arm Prosthesis”