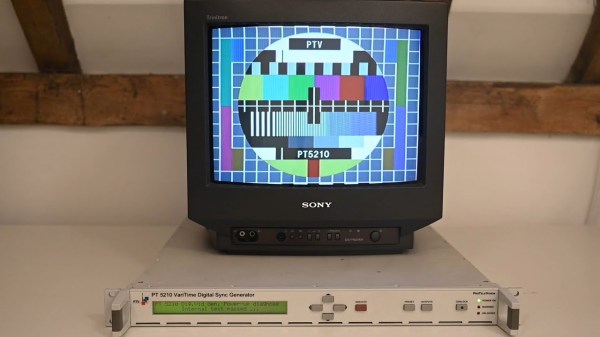

Over the years, we’ve seen a good number of interfaces used for computer monitors, TVs, LCD panels and other all-things-display purposes. We’ve lived through VGA and the large variety of analog interfaces that preceded it, then DVI, HDMI, and at some point, we’ve started getting devices with DisplayPort support. So you might think it’s more of the same. However, I’d like to tell you that you probably should pay more attention to DisplayPort – it’s an interface powerful in a way that we haven’t seen before.

You could put it this way: DisplayPort has all the capabilities of interfaces like HDMI, but implemented in a better way, without legacy cruft, and with a number of features that take advantage of the DisplayPort’s sturdier architecture. As a result of this, DisplayPort isn’t just in external monitors, but also laptop internal displays, USB-C port display support, docking stations, and Thunderbolt of all flavors. If you own a display-capable docking station for your laptop, be it classic style multi-pin dock or USB-C, DisplayPort is highly likely to be involved, and even your smartphone might just support DisplayPort over USB-C these days. Continue reading “DisplayPort: A Better Video Interface”