Whenever a product becomes popular, it’s only a matter of time before other companies start feeling the urge to hitch a ride on this popularity. This phenomenon is the primary reason why so many terrible toys and video games have been produced over the years. Yet it also drives the world of electronics. Hence it should come as no surprise that ST’s highly successful ARM-based series of microcontrollers (MCUs) has seen its share of imitations, clones and outright fakes.

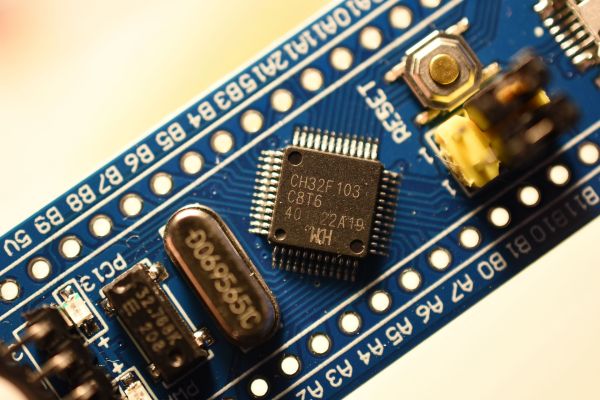

The fakes are probably the most problematic, as those chips pretend to be genuine STM32 parts down to the markings on the IC package, while compatibility with the part they are pretending to be can differ wildly. For the imitations and clones that carry their own markings, things are a bit more fuzzy, as one could reasonably pretend that those companies just so happened to have designed MCUs that purely by coincidence happen to be fully pin- and register compatible with those highly popular competing MCU designs. That would be the sincerest form of flattery.

Let’s take a look at which fakes and imitations are around, and what it means if you end up with one. Continue reading “STM32 Clones: The Good, The Bad And The Ugly”