Of all the people I was looking forward to meeting at Supercon, aside from my Hackaday colleagues with whom I had worked for five years without ever meeting, was a fellow from Germany named Matthias Balwierz. The name might not ring a bell, but he’ll certainly be familiar to Hackaday readers as Bitluni, the sometimes goofy but always entertaining and enlightening face of “Bitluni’s Lab” on YouTube.

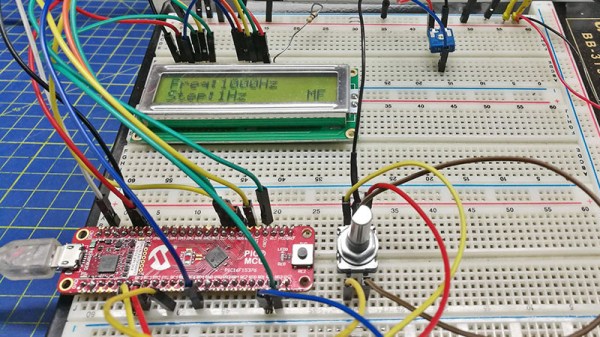

I’d been covering Bitluni’s many ESP32 hacks over the years, and had struck up a correspondence with him, swapping ideas and asking for advice on the many projects I start but somehow never finish. Luckily for us, Bitluni is far better on follow-through than I am, and he brought that breadth and depth of experience to the Design Lab stage for that venue’s last talk of the 2019 Superconference, before the party moved next door for the badge-hacking presentations.

Continue reading “Bitluni Brings All The ESP-32 Multimedia Hacks To Supercon”