Magnets have always been fun, particularly since the super-powerful neodymium type became readily available. You can stack them up, pull them apart, or, if you really want, use them for something practical. Now [Adric] has shown us a new use for them entirely – by writing hidden messages on them.

It’s a remarkably simple hack, but ingenious all the same. [Adric] was pretty sure that the Quelab hackerspace laser wasn’t powerful enough to cut or etch a nickel-plated neodymium magnet. However, they suspected it would have just enough power to heat localised parts of the magnet above the Curie temperature, where the magnetic properties of the material break down.

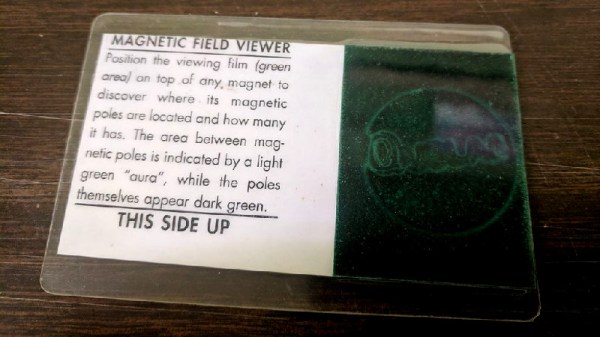

Thus, the laser cutter was set up to run a few passes over some neodymium magnets. By placing a magnetic viewing film over the magnet, it’s possible to make the etched pattern visible. There was also some incidental visible marking of the magnet surface, which [Adric] thinks is due to the tape applied to the magnet before the laser processing.

For those of you operating spy rings in deep cover, you’ve now got a new way to send them secret messages. Just be sure to check in with the local postal service as to their policies regarding giant magnets in the post. Then you can contemplate whether you have the ability to sense magnetic fields.