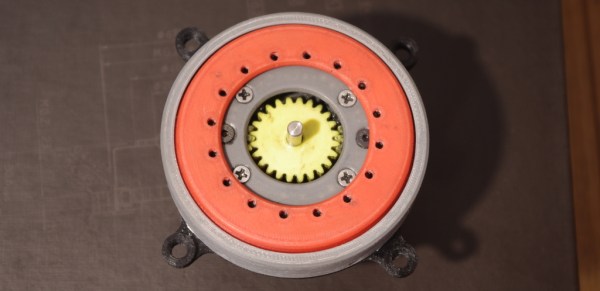

Artist Pe Lang uses linear polarization filters to create an unusual effect in his piece polarization | nº 1. The piece consists of a large number of discs made from polarizing film that partially overlap each other at the edges. Motors turn these discs slowly, and in the process the overlapping portions go from clear to opaque black and back again.

The disc rotation speed may be low but the individual transitions occur quite abruptly. Seeing a large number of the individual discs transitioning in a chaotic pattern — but at a steady rate — is a strange visual effect. About 30 seconds into the video there is a close up, and you can see for yourself that the motors and discs are all moving at a constant rate. Even so, it’s hard to shake the feeling of that one is watching a time-lapse. See for yourself in the video, embedded below.

Continue reading “This Art Project’s Video Is Not A Time-Lapse”