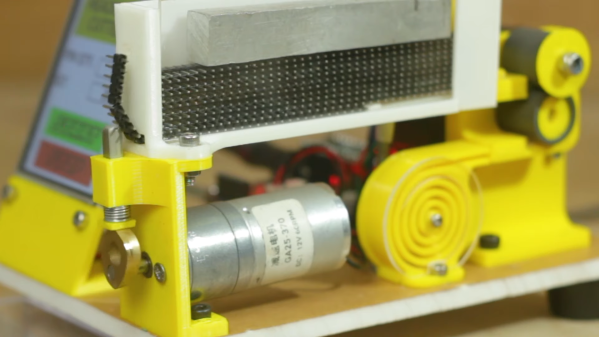

If there’s something more tedious than winding coils, we’re not sure what it is — possibly rolling and wrapping coins; that’s really a bother. But luckily, just like there are mechanical ways to count coins, there are tools to make coil production a little less of a chore, but perhaps none that have as much charm as this all-mechanical coil winder.

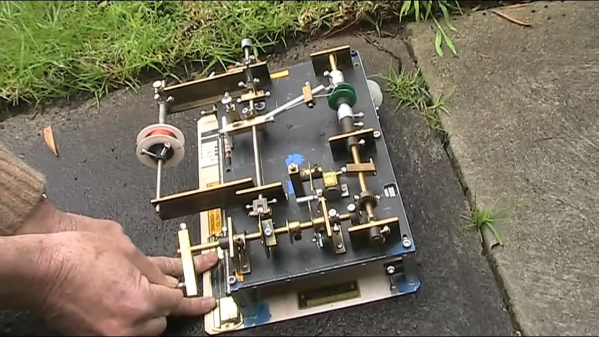

We’d say that [Ralph (VK3ZZC)]’s amazing invention firmly falls under the “contraption” category, without a hint of the term being used as a pejorative. The rig was based on the MoReCo Coilmaster, a machine that was once commercially available at a fairly steep price, according to [Ralph], and still seems to command a premium even today. Never being able to afford an original, [Ralph] spun up his own from scrap metal and tooling no more sophisticated than a drill press. It’s a riot of brass and steel, with a hand crank that drives the main winding shaft while powering a cam that guides the wire along the long axis of the coil form. Cams can be changed out for different winding patterns, and various chucks adapt to hold different coil forms to the winding shaft.

Continue reading “All-Mechanical Coil Winder Is A Scrap-Bin Delight”