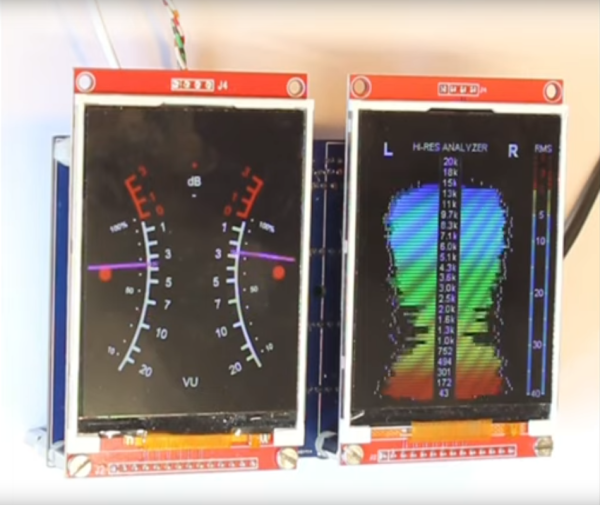

While high-fidelity audio has come a long way in the past several decades, a lot of modern stereo equipment is still missing out on some of the old analog meters that were common on amplifiers and receivers of the 60s through the 80s. Things like VU meters don’t tend to be common anymore, but it is possible to build them back in to your sound system with the help of some microcontrollers. [Mark] shows us exactly how to reclaim some of the old-school functionality with this twin audio visualizer display.

Not only does this build include two displays, but the microcontroller is keeping up with 170 channels in real-time in order to drive the display. What’s more impressive is that it’s being done all on a Teensy 4.1. To help manage all of the data and keep the speed as fast as possible it uses external RAM soldered to the board, and a second Teensy audio board is used to do the real time FFT analysis. Most of the channels are sent to the display hosting the spectrum analyzer but two are reserved for left and right stereo VU meters on the second display.

The project from [Mark] is originally based on this software from [DIYLAB] so everything is open-source. While it was originally built for a specific piece of hardware, [Mark] has it set up with a line in and line out plus a microphone input so it can be used for virtually any audio hardware now. For another take on the classic VU meter, take a look at this design based on an Arudino instead.

Continue reading “Teensy Spectrum Analyzer Has 170 Channels”