If you hang around Hackaday long enough, pretty soon you’ll start to see some patterns emerging. As the nexus of all things awesome in the hacking world, our front page offers a unique vantage point by which you can see what’s getting folks excited this particular month, year, or decade. Right now we can tell you hackers love the Raspberry Pi, 3D printing, and perhaps above all, they can’t get enough mechanical keyboards.

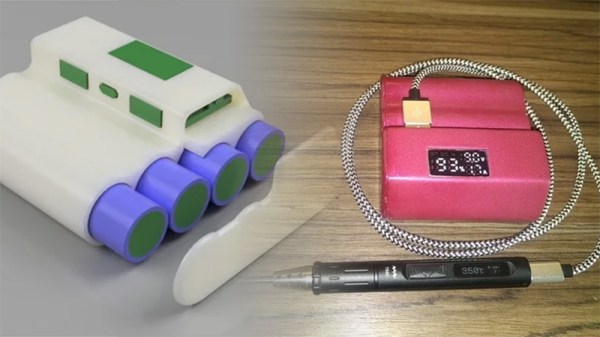

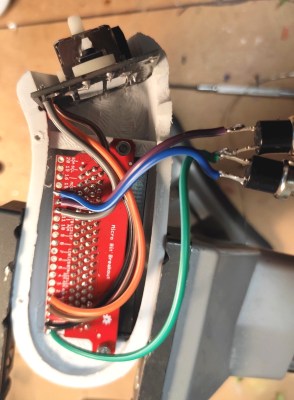

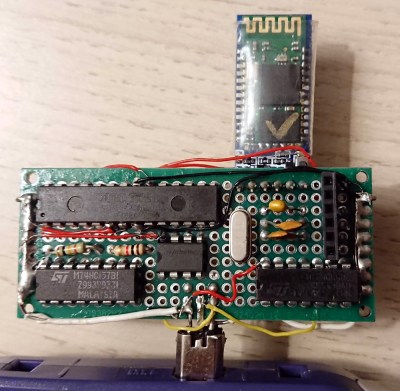

So that makes the Jazzberry by [Mattis Folkestad] something of a perfect storm in the hacker world. The project uses a 3D printed enclosure to combine a Raspberry Pi 3B+ and an Ajazz AK33 mechanical keyboard into a single unit like the home computers of old. Honestly, we’re just glad he didn’t sneak an ESP8266 in there; as the resulting combination might have been enough to crash the site.

So that makes the Jazzberry by [Mattis Folkestad] something of a perfect storm in the hacker world. The project uses a 3D printed enclosure to combine a Raspberry Pi 3B+ and an Ajazz AK33 mechanical keyboard into a single unit like the home computers of old. Honestly, we’re just glad he didn’t sneak an ESP8266 in there; as the resulting combination might have been enough to crash the site.

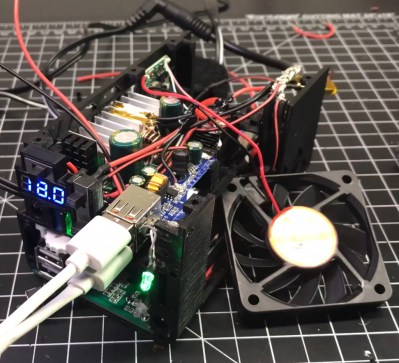

That being said, we can’t help but notice there’s a lot of open space inside the 3D printed enclosure. Right now there’s nothing inside but the Raspberry Pi, which only takes up a fraction of the internal volume. Adding a battery and hard drive would be the logical next steps, but it could also be outfitted with a suite of radios and various other hacking and security research accoutrements. We’ve seen an influx of such builds over the last few months, and the Jazzberry seems like it could make a very slick entry into this burgeoning category of mobile pentesting devices.

The STL files are designed specifically for the combination of hardware that [Mattis] used, but it shouldn’t be too difficult to modify them for your own purposes. Even if you stick with the same AK33 keyboard, an upgrade to the impressively powerful Raspberry Pi 4 would be more than worth the time fiddling with the STLs in your CAD tool of choice. If you really want to go all in, add a display and you’re well on the way to that cyberdeck you’ve always wanted.