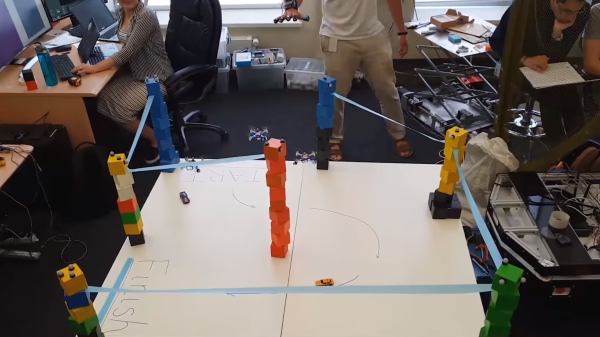

Sometimes one just needs an extra hand or six around the workbench. Since you’re a hacker that should take the form of a tiny robot swarm that can physically display your sensor data, protect you against a dangerously hot caffeine fix and clean up once you’re done. [Ryo Suzuki] and [Clement Zheng] from the University of Colorado Boulder’s ATLAS Institute developed ShapeBots, small shape-shifting swarm robots that aim to do exactly that and more.

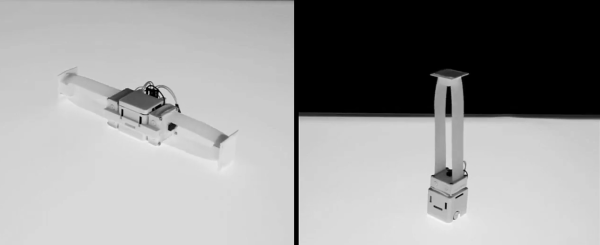

The robots each consist of a cube shaped body with 2 small drive wheels, onto which 1-4 linear actuator modules can attach in various positions. For control the robots’ relative positions are tracked using an overhead camera and is shown performing the tasks mentioned above and more.

To us the actuators are the interesting part, consisting of two spools of tape that can extend and retract like a tape measure. This does does lead us to wonder: why we haven’t seen any hacks using an old tape measure as a linear actuator? While you likely won’t be using it for high force applications, it’s possible to get some impressive long reach from a small from factor. This is exactly what the engineers behind the Lightsail 2 satellite used to deploy it’s massive space sail. Space the two coils some distance apart and you can even achieve full 2-axis motion.

You can also control your swarm using your favourite wifi chip or have them skitter around using vibration or 3D print some linear actuators.

Thanks for the tip [Qes]!