Geiger counters are a popular hacker project, and may yet prove useful if and when the nuclear apocalypse comes to pass. They’re not the only technology out there for detecting radiation however. Scintillation detectors are an alternative method of getting the job done, and [Alex Lungu] has built one of his own.

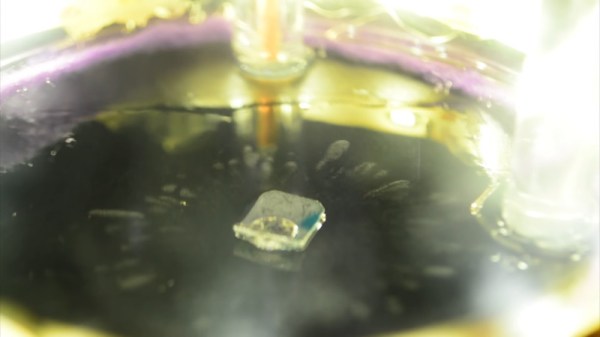

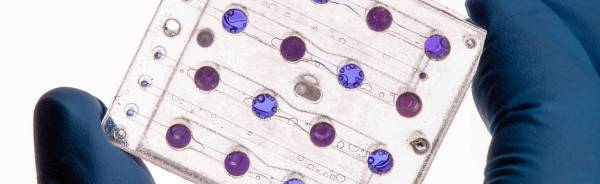

Scintillation detectors have several benefits over the more common Geiger-Muller counter. They work by employing crystals which emit light, or scintillate, in the presence of ionizing radiation. This light is then passed to a photomultiplier tube, which emits a cascade of electrons in response. This signal represents the level of radioactivity detected. They can be much more sensitive to small amounts of radiation, and are more sensitive to gamma radiation than Geiger-Muller tubes. However, they’re typically considered harder to use and more expensive to build.

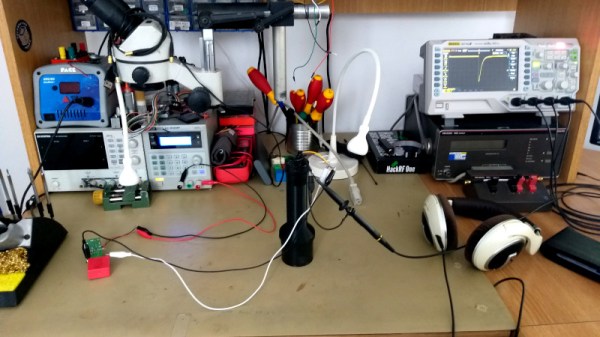

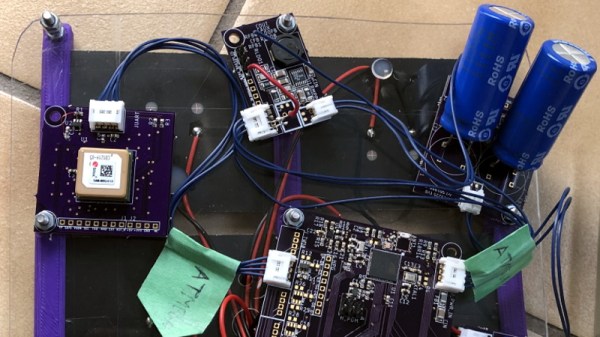

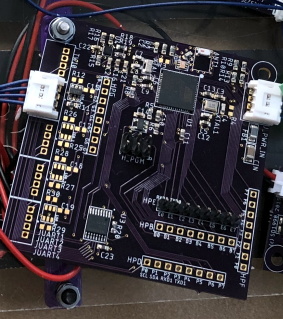

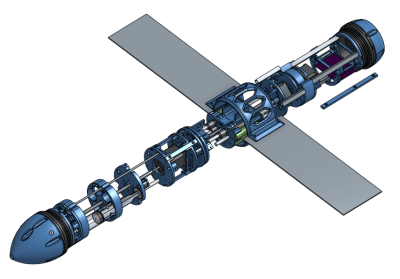

[Alex]’s build uses a 2-inch sodium iodide scintillator, in combination with a cheap photomultiplier tube he scored at a flea market for a song. [Jim Williams]’s High Voltage, Low Noise power supply is used to run the tube, and it’s all wrapped up in a tidy 3D printed enclosure. Output is via BNC connectors on the rear of the device.

Testing shows that the design works, and is significantly more sensitive than [Alex]’s Geiger-Muller counter, as expected. If you’re interested in measuring small amounts of radiation accurately, this could be the build for you. We’ve seen this technology used to do gamma ray spectroscopy too.