For most Hackaday readers the process of buying groceries this weekend has been a relatively painless one, however we’re guessing some of our German friends will have found their cards unexpectedly declined. The reason? A popular model of payment card terminal, the Verifone H5000, has suffered what has been described as a “software malfunction”. So exactly what has happened? The answer is as simple as it is unfortunate: a security certificate for German transaction processing stored on the device has expired.

The full story exposes the flaws in assuming that a payment terminal is an appliance rather than a computer and its associated software that needs updating like any other. The H5000 is an old terminal that ceased production back in the last decade and has reached end-of-life, however it has remained in use and perhaps more seriously, remained in the supply chain to merchants buying a terminal. With updates requiring a site visit rather than an over-the-air upgrade, it’s likely that the effects of this mess could last a while.

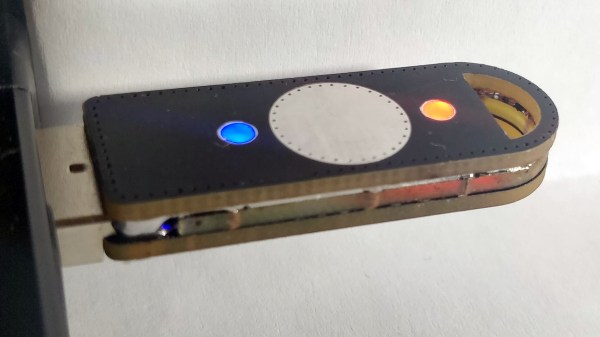

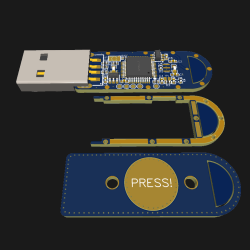

In case the hardware for this type of equipment interests you, we’ve had a teardown on another Verifone terminal in the past.