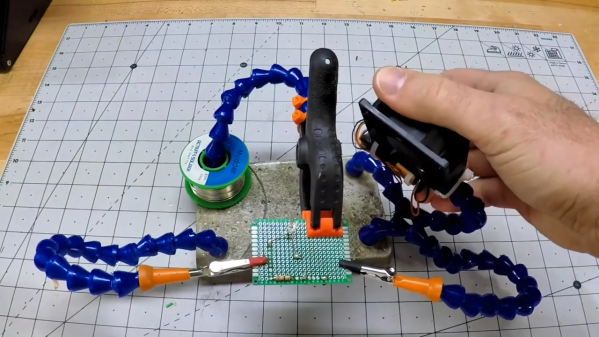

[ctstarkdesigns] had fond memories of collecting maple syrup as a child. At the same time, he also remembered the work involved: from lugging buckets around on an unstable snow mobile to accidentally burning the mixture and making all the effort for naught. So he set out to make things a little easier this time around by building his own evaporator.

The build starts as many do, with a surplus 44-gallon drum. With an off-the-shelf kit, and some cutting and welding, it’s readily repurposed into a stove capable of burning wood in a roaring fire. From there, it’s a simple matter of making a few further incisions to install warming trays, used to hold the takings from the maple trees. There, the mixture can be boiled down into the tasty, delicious substance that goes so perfectly on pancakes.

The build has the dual benefits of both easing the boiling process and keeping the user warm while doing so. Already, the rig has proven itself as an adept heater, and we’re sure it will only prove more popular once it’s producing sweet maple syrup en mass. If that’s not enough, consider building an entirely automated system in your back yard!