Electroplating is a great way to add strength or shine to a 3D print. However, we don’t see too many people trying it with gold. [HEN3DRIK] isn’t afraid to experiment, though, and pulled off some amazing, high-quality jewelry-grade plating!

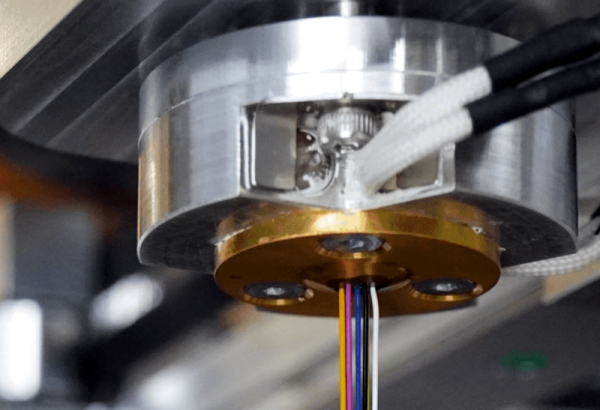

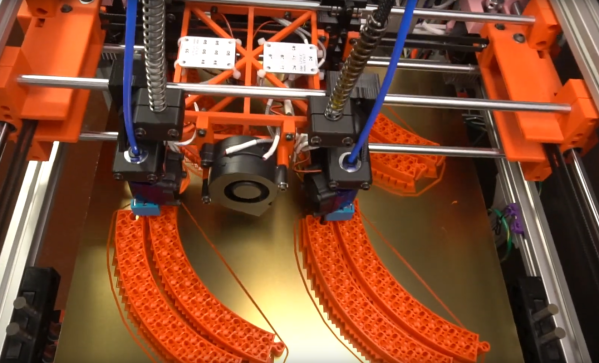

The design for the project was the so-called Ring of Power from Lord of the Rings. The print was created on a resin printer at a high quality level, washed thoroughly to remove any remaining resin, and then cured. The print was then post-processed with sandpaper to make it as smooth as possible. Conductive paint was then applied, ready to take on the plating layers. [HEN3DRIK] first started by plating copper to build up a tough base layer, then nickel to prevent mixing between the copper and gold. The gold is then finally plated on top. Plating the copper is done with the ring constantly rotating to get as even a coat as possible. In contrast, the gold plating is done with a brush to avoid wasting the highly-expensive plating solution.

The final result is a gleaming gold ring that probably feels strangely light in the hand. The technique is time consuming, thanks to the need to plate multiple layers, but the results are to die for. We’ve seen [HEN3DRIK]’s fine work before, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Making The One Ring By Electroplating Gold On A 3D Print”