Very slowly, some very cool parts are coming out on the market that will make for some awesome builds. Supercapacitors are becoming a thing, and every year, the price of these high power supercaps go a little lower, and the capacity gets a little higher. It’s really only a matter of time before someone hacks some supercaps into an application that’s never been seen before. The Navy is doing it with railguns, and [David] is building an electric bike, powered by AA batteries. While [David]’s bike technically works with the most liberal interpretation of ‘technically’, it’s the journey that counts here.

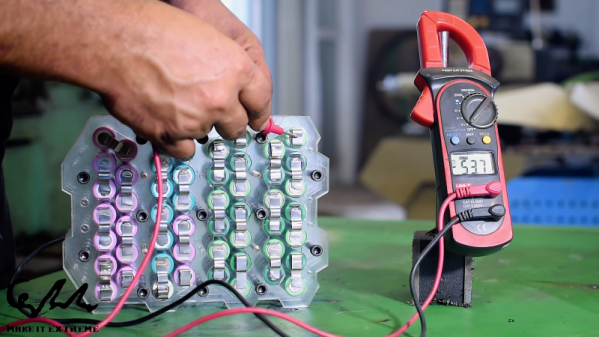

This project began as an investigation into using supercapacitors in an electric bicycle. Supercaps have an energy density very much above regular capacitors, but far behind lithium cells. Like lithium cells, they need a charge balancer, but if you manage to get everything right you can trickle charge them while still being able to dump all that power in seconds. It’s the perfect application for a rail gun, or for slightly more pedestrian applications, an electric bike with a hill assist button. The idea for this build would be to charge supercaps from a bank of regular ‘ol batteries, and zoom up a hill with about fifteen seconds of assistance.

The design of the pulsed power DC supply is fairly straightforward, with a mouthful of batteries feeding the supercap array through boost regulators, and finally going out to the motor through another set of regulators. Unfortunately, this project never quite worked out. Everything worked; it’s just this isn’t the application for the current generation of supercapacitors. There’s not enough energy density in [David]’s 100F supercaps, and the charging speed from a bunch of AA batteries is slow. For fifteen minutes of charging, [David] gets about fifteen seconds of boost on his bike. That’s great if you only ever have one hill to climb, but really useless in the real world.

That doesn’t mean this project was a complete failure. [David] now has a handy, extremely resilient array of supercaps that will charge off of anything and provide a steady 24V for a surprising amount of time. Right now, he’s using this scrapped project as a backup power supply for his 3D printer. That 100 Watt heated bed slurps down the electrons, but with this repurposed supercap bank, it can survive a 20 second power outage.

It’s a great project, and even if the technology behind supercaps isn’t quite ready to be used as a boost button on an electric bike, it’s still a great example of DIY ingenuity. You can check out [David]’s demo of the supercap bank in action below.

Continue reading “Fail Of The Week: An Electric Bicycle, Powered By AA Batteries” →