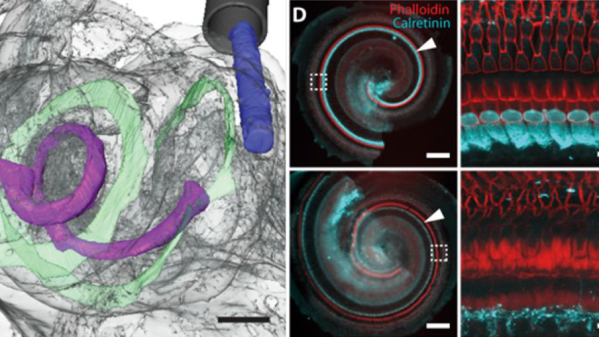

Eyes are windows into the soul, the old saying goes. They are also pathways into the mind, as much of our brain is involved in processing visual input. This dedication to vision is partly why much of AI research is likewise focused on machine vision. But do artificial neural networks (ANN) actually work like the gray matter that inspired them? A recently published research paper (DOI: 10.1126/science.aav9436) builds a convincing argument for “yes”.

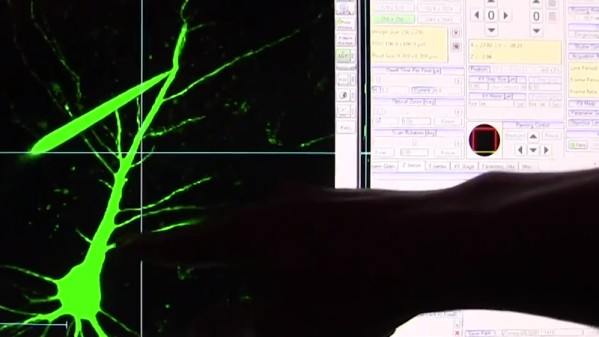

Neural nets were named because their organization was inspired by biological neurons in the brain. But as we learned more and more about how biological neurons worked, we also discovered artificial neurons aren’t very faithful digital copies of the original. This cast doubt whether machine vision neural nets actually function like their natural inspiration, or if they worked in an entirely different way.

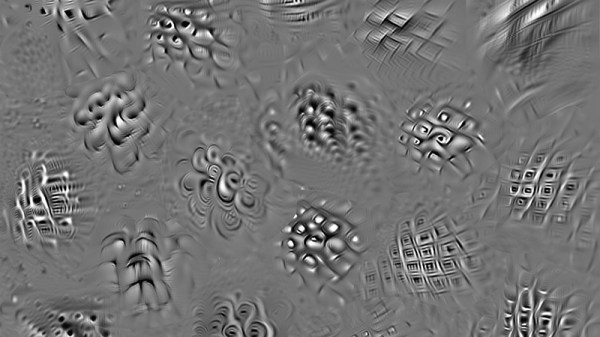

This experiment took a trained machine vision network and analyzed its internals. Armed with this knowledge, images were created and tailored for the purpose of triggering high activity in specific neurons. These responses were far stronger than what occurs when processing normal visual input. These tailored images were then shown to three macaque monkeys fitted with electrodes monitoring their neuron activity, which picked up similarly strong neural responses atypical of normal vision.

Manipulating neural activity beyond their normal operating range via tailored imagery is the Hollywood portrayal of mind control, but we’re not at risk of input injection attacks on our brains. This data point gives machine learning researchers confidence their work still has relevance to biological source material, and neuroscientists are excited about the possibility of exploring brain functions without invasive surgical implants. Artificial neural networks could end up help us better understand what happens inside our brain, bringing the process full circle.

[via Science News]